Review: Dancing at Lughnasa by Brian Friel. Directed by Sheila Daniels. With Mari Nelson, Linda K. Morris, Gretchen Krich, Elizabeth Raetz, Cheyenne Casebier, Troy Fischnaller, Benjamin Harris and Todd Jefferson Moore. Now through December 5 at Seattle Rep.

|

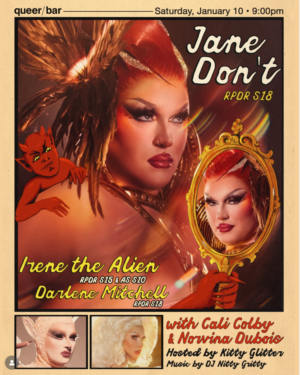

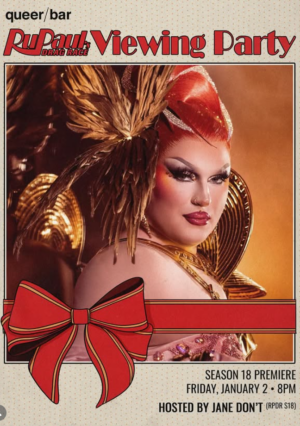

| (l-r) Linda K. Morris, Elizabeth Raetz, Mari Nelson, Cheyenne Casebier, and Gretchen Krich to star in Dancing at Lughnasa. Photo by Keri Kellerman. |

I’ve heard of Brian Friel’s Dancing at Lughnasa (of course) but I haven’t seen a production of the play, or the film, or even read it so I went into it fairly blind as to its content other than knowing it was about a family of sisters in Ireland and they like to dance and it won a lot of awards and is considered an “Important Serious Play” and it’s frequently staged by big regional theater companies. But, I’m of the school that doesn’t pay much attention to reputations; plenty of dreadful plays, films and books have won awards and acclaim…it doesn’t mean they are good… it only means that they are popular in the context of the time in which they made their debuts. But, time usually tells, and mediocre work usually fades from view.

I don’t think Dancing with Lughnasa is mediocre. It has some beautiful writing and five very strong roles for women. It is frequently moving but it also has a strong sense of humor and it features several powerful moments including a spine tingling dance number when the women of the play dance a passionate Irish jig while listening to their beloved wireless. It is also oddly paced with an old fashioned clunky framework and the male characters are moronic cartoons. There are several plot holes in the script and far too many bits of twee Irishness that border on characterture. (It is my firm belief that Ireland is as frequently misrepresented in all forms of media as the American South: broad, overdrawn characters and situations that belittle the actual charm and complexity of those regions.) And, that big spine tingling dance number occurs halfway through the first act of the play…we never again reach those same heights of passion and drama; you might as well leave the theater after that moment. It is never recaptured and while acclaimed Seattle director Sheila Daniels tries her best to shape this play into a coherent whole, she never succeeds. And, I don’t think it’s her fault; the play never succeeds on its terms as a text.

Lughnasa is a memory play and it’s (mostly) playwright Brian Friel’s memories we are being fed, via his surrogate, Michael who wanders the stage as a young adult recounting the lives of his mother and her four sisters during the summer of 1936 in their remote, impoverished Irish community of Ballybeg. Michael is a bastard and his mother Christine has to bear the stigma of being an unwed mother in Roman Catholic Ireland. They live with Christine’s four sisters on the family farm: the mentally slow Rose, the frustrated needle worker Agnes, the earthy cook Maggie and the family matriarch, big sister Kate who largely supports the family on her teacher’s salary. The family is preparing for the arrival of their brother, Father Jack who is returning from missionary work in Africa and to recuperate from malaria, and also dealing with the sudden appearance of Michael’s immature father, the roguish Gerry who still manages to kindle the flame in Christine’s heart. But, as we learn from Michael, this is the last “Lughnasa” festival the family will enjoy. Events conspire that will tear the family apart. (No one ever promised these would all be happy memories.)

I’m not a fan of “memory plays” or narrators in general wandering around the fringes of plays filling us in on information that could be better conveyed through dialogue and text. When done well, it can be brilliant, but it’s such an old school theatrical device and “Lughnasa” isn’t that old of a play (1990). The character of Michael just feels clunky and unnecessary and frankly, he’s a bit of a bore, even when he’s rather morosely filling us in on the eventual tragic outcomes for most of the the characters. He gets in the way of the heart of the story, the relationships of the five sisters with one another and the outside world. I don’t much care about Father Jack and the revelation that life in Africa has reverted him to a pagan, or the antics of the immature baby daddy, Gerry. Neither character felt very real and while they provide entertaining moments, they are more distraction than attraction. It’s a show about the sisters. I want to hear them talk, and I want to see them dance. Those moments are the only ones of genuine dramatic interest and charm in the show and there are not enough of them. We need to learn why these women are so stunted emotionally and why they remain trapped in their circumstances. Yes, they are poor women in a poor country in the middle of the Depression but there are always options. The play never digs deep enough to explore their lives; it’s too busy dragging the men into the picture and having them wear funny hats.

I’m not fond of the text but individually there are fine moments in this play provided by the talent involved. All the actors in this production gave excellent performances, despite the limitations of their characters and each gets a moment to show their worth. (One of the problems of this play is that it’s just a series of moments; nothing coheres into anything very long lasting or meaningful.) I’m not a fan of the male characters, but Benjamin Harris as the young narrator Michael, Troy Fischnaller as the ne’er do well Gerry and especially Todd Jefferson Moore as the paganistic priest, Father Jack all gave strong performances and were assets to the production despite the limitations of the characters.

But, the show is dominated by the five sisters and each actress gave powerful and enthusiastic performances. As the youngest sister, Chris, Elizabeth Raetz has to alternate charming naivete with hopeless despair and she handles the changes in mood with great confidence and clarity. Cheyenne Casebier nicely underplays the “slow” sister Rose and creates a believable portrait of a woman who might be emotionally and cognitively challenged but still retains her own sense of self. And, Linda K. Morris as her older sister Agnes, the selfless protector of Rose, nicely plays that quiet inner strength required to care for the challenged, as well as the subtle longing she has for her sister’s beau Gerry. It’s a lovely, carefully nurtured performance.

Gretchen Krich’s earthy, fun-loving Maggie was undoubtedly the audience favorite for her bawdy turn as the family cook but was equally moving in her moments when she recalled her own lost moment of happiness and the path taken by a childhood friend of hers. The role is lovingly written and Ms Krich gives a lovingly rendered performance of the character, a role she’s played elsewhere. It’s the kind of performance that wins actresses well deserved rewards.

But, the flinty heart and soul of “Lughnasa” belongs to Kate, the practical bread winning head of the family and Mari Nelson is compelling as the toughly tender Big Sister of the clan. Kate is tough, smart and better educated than her siblings and she could clearly do better in life but her loyalty and devotion to her family is sacrosanct and she will protect them at all costs. Ms Nelson plays Kate with a razor sharp clarity and singularity of purpose but she is not afraid to expose the soft underbelly of Kate, the moments when Kate wants to give in to frivolity, or romance, or mischief. Her Kate is multi-dimensional and fascinating and real to behold and you leave the theater wanting to know more about the character and her fate.

I usually praise sets and seldom pan them, (I usually just ignore things that don’t make any impression) but I have to say I wasn’t a big fan of Etta Lilienthal’s set which consists of two walls of the tiny family cottage, a huge terraced yard and a rather alarmingly large hillside looming over the house. I understand the need to make the house appear small and crowded, but the playing area for the actors was too small and led to some awkward staging. The bleakness of the design was impressive, but it seemed impractical and the looming hillside seemed a bit forced and highly artificial. It just wasn’t my cup of tea.

I can say the same for Dancing at Lughnasa. It has its moments, a powerful feeling of sisterhood and some excellent performances but it seems like it needs more than that. Like many Americans, I’ve got Irish blood in me. Except for the empowering dance in Act I, that blood was never really stirred for me in this play. It’s a series of moments that never quite coalesce into a meaningful whole.

– Michael Strangeways