Amontaine Aurore’s powerful play (Don’t Call It a Riot!) just finished up an eight-show run, but plans to revive it are in the works; and the Photographic Center Northwest and Frye Art Museum team up for a visual display honoring the Party.

I have a thing against playwrights directing their own shows. Even if they’re talented in both capacities, as an audience member I appreciate having an intermediary interpret the playwright’s work. When there’s a third party to serve as a filter (assuming they truly understand the work and the playwright’s vision), it seems to make for a much sharper piece.

I found an exception to my rule in Amontaine Aurore’s beautiful staging of her new play, “Don’t Call It a Riot!”, which focuses on two generations of activism in Seattle: the Black Panther Party for Self Defense and the WTO protests, and particularly Black women’s roles in each.

The play tells the big story through small, highly personal ones, set primarily in two living rooms; and while the living room stories of the characters are invented, the big stories they share are quite true.

In 1968, they play’s two main characters, Reed and Marti, live in Seattle’s Central District, where the two young Black women are energetic members of the Black Panther Party. Aaron Dixon, a local Party Captain, had just been arrested; after police ransacked party headquarters, they found no evidence of violent overthrow as alleged, but did find a typewriter they claimed had been stolen. So the long-term unrest boiled over into the streets. The Seattle Police Department (or “Seattle Pig Delegation,” as they’re alternately described in the play) corners protesters and shuts them down with mass arrests. Dixon was later acquitted.

Meanwhile, Reed is pregnant with her first child, a daughter she’ll name Falala, as her partner Sam, another Party member, traverses the West Coast, learning of the Bay Area Panthers’ tactics in order to establish Seattle’s own free breakfast program to keep the area’s children from going to school hungry. Marti has moved in with Reed in order to help her through her pregnancy with Sam on the road — and because her family kicked her out after she’s caught shoplifting a dress that was “love at first sight,” and has nowhere else to go.

Marti is a reluctant Party member, more interested in fashion than revolution; it’s hard to tell exactly why she joined the Party, but that it was fashionable with her friends is a good possibility. Reed and Sam, meanwhile, are true believers, committed to the cause and the revolution.

Flash forward three decades to 1999, and not all has gone as planned. The Party has dissolved, taken down by FBI infiltration and resulting paranoia and infighting. Reed and Marti reunite but hardly recognize each other. And Falala is carrying the activist torch, now in the WTO protests flooding through Downtown Seattle; her (white) boyfriend is a masterful mansplainer; and Sam is no longer in the picture.

What follows is a painful process of untangling lies, and parsing out the (big-picture and small-picture) values that mean most to each of them.

As playwright, Aurore deftly wove activism and values playing both in the streets and in living rooms (the political meeting the personal, as the saying goes). As director, her choices kept both the personal and political moving along quickly, snappy in dialog, and playing very close and urgently to the audience.

The piece centered on women, and the females in the cast — Meysha Harville (younger & older Reed), Lillian Afful-Straton (younger & older Marti), and Skylar Wilkerson (Falala) — carried the lion’s share of the show. Their dynamic between each other was fantastic; Harville’s Reed and Afful-Straton’s Marti skillfully hopped eras and changed personalities; and Wilkerson’s Falala was right-on in navigating between passionate activist and, occasionally, super-brat.

The men, with much smaller roles, made them nonetheless memorable: the revolutionary passion of Sam (played by Mic Montgomery, Gregory Award-nominated for his role in the acclaimed Theatre Battery show, Hooded, or Being Black for Dummies) drew a thunderous response from the audience; and Robert Lovett (as Falala’s boyfriend, Paris) showed such a strong aptitude for mansplaining on stage it may become legendary — along with a fair dose of caring, too.

The tiny theatre at 18th & Union (which was a packed house) and the design work helped facilitate that intimate feel the script needed as well: and the set, designed by Gregory Award-winning Margaret Toomey, kept the actors playing practically in the lap of the front row. The short scenes, separated and punctuated by near-full blackouts, moved along nicely and had the audience cheering between scenes, much like the live-audience sitcoms of olde; and the changed-era music was a brilliant shorthand signal of the passage of time.

Don’t Call It a Riot! has closed its run, but there are rumors of both a tour and a remount in Seattle. This run was a culmination of development in Seattle, including a workshop reading at the venerable Theatre Battery in Kent (never before thought I’d use “venerable” and “Kent” so closely connected in a sentence, but here we are), and a big-stage performance at last summer’s Nights at the Neptune, put on by Seattle Theatre Group.

With the energy coming from the actors and thrown back to them from the audience, and with the urgent need for values and hunger for activism in the present day, Don’t Call It a Riot! shows no signs of slowing down. Nor should it.

To follow the playwright’s latest projects and hear where the play will head next, you can view Aurore’s website, here.

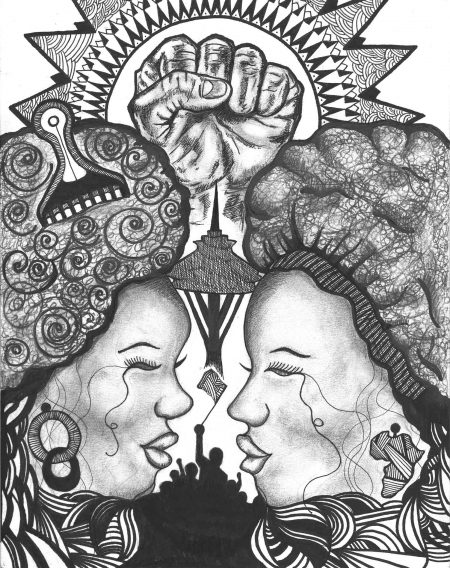

From the exhibit, All Power: Visual Legacies, on display at Photographic Center Northwest. Art by Emory Douglas (left), Ouidakathryn Bryson (center), and unknown (right). (Photo by R Barron)

Activities Honoring Seattle’s Black Panther Party

Aurore’s production comes during the 50th anniversary of the founding of the Party’s Seattle chapter, one of the earliest; the play was one of several activities commemorating the Party. A symposium was held last month at Washington Hall, and the celebration continues with a photo exhibit at Photographic Center Northwest and related programming at the Frye Art Museum (both in the First Hill area).

At Photo Center NW, the exhibit All Power: Visual Legacies of the Black Panther Party runs through June 10th. Admission to the Center’s gallery is always free; hours are Monday-Thursday 12-9pm, Saturday-Sunday 12-6pm (closed Fridays). Find more information here.

At the Frye, one related program remains. On June 9, the museum will hold a panel, All Power: Visual Legacies of the Black Panther Party – Local Impact, featuring Royal Alley-Barnes and King County Councilman Larry Gossett (one of the “Gang of Four” activists), and moderated by Photo Center NW director and curator, Michelle Dunn Marsh. Admission to the Frye is always free; panel runs from 2-3:30. Find more information here.