The genre bending theater artist TAYLOR MAC comes to Seattle’s Moore Theatre this Friday, April 20 with an installment of his award winning, “A 24-Decade History of Popular Music”.

For one night — Friday, April 20th — celebrated queer artist Taylor Mac (playwright, actor, singer-songwriter, performance artist) will bring a three-decades-long segment of the epic A 24-Decade History of Popular Music to Seattle, at the Moore Theater. The work was a finalist for the 2017 Pulitzer Prize in Drama, and won the Kennedy Prize for Drama. Mac also became a MacArthur Fellow in 2017, for “Engaging audiences as active participants in works that dramatize the power of theater as a space for building community.”

Tickets are a very-reasonable $25-$35, and some are still available. If you want them, you should probably get them now.

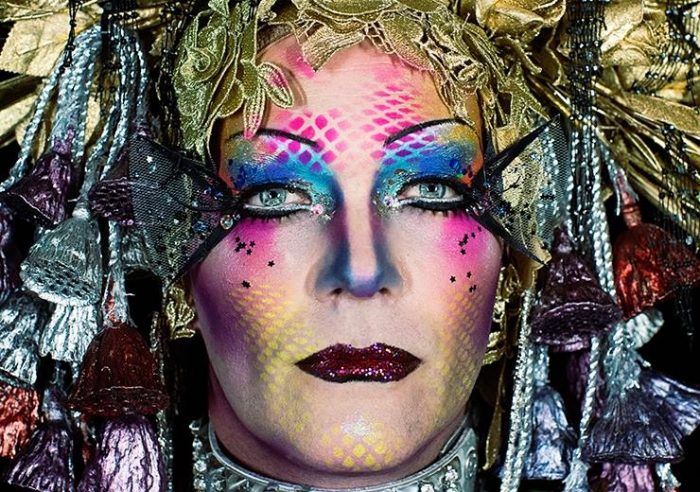

The show tells history through three decades (1956-1986) of American popular music that, in Mac’s view, define the decades — in a form all reimagined, queered up, and adorned in fantastical costumes from designer and long-time creative collaborator Machine Dazzle.

[Machine Dazzle was kind enough to sit down for a phone interview in anticipation of the Seattle performance; you can read pieces from our conversation here.]

The show covering 1956-1986 will run three hours, at least, with one hour devoted to each of the three decades, and one elaborate, life-of-its-own costume for each. The musical reinterpretations were were arranged with music director Matt Ray, who also leads Mac’s on-stage band. Detroit-based singers Steffanie Christi’an and Thornetta Davis will join them.

If the three-hour show sounds like a lot, you should know that this piece is merely one act — Act VII, to be exact — of a much longer whole. The full performance of A 24-Decade History of Popular Music runs a full 24 hours which, as the name suggests, covers all 24 decades of America’s history as a stand-alone nation (1776 until the show’s premiere in 2016).

A single 24-hour rendition of the full material is not Mac’s normal delivery method — though it did happen, in October 2016 at St. Ann’s in New York, the culmination of many shorter-but-still-long versions Mac viewed as “training” for the full marathon that followed. More commonly, Mac will either run a series of four (six-hour) shows or eight (three-hour) shows, one per night, to span the full composition or, as here, bring a segment of the overall piece, focusing on a concentration of decades or an abridged version of the whole.

For the one-night, three-hour Seattle show, the decades on display will be 1956-1986 — and as far as political upheaval, social change, and excellent music go, it’s hard to argue with that selection of decades.

Form vs. Content

“The youth don’t understand you can’t mess with content and form at the same time,” says the character Paige in the 2015 Mac play Hir (read a discussion of it here). Though Mac would likely take the line tongue-in-cheek, A 24-Decade History appears in line with that advice nevertheless.

(As an example of Mac happily playing with form and content at the same time, one of Mac’s gender pronouns is the lowercase name judy — as in Judy Garland — in recognition that Mac’s performative work in 24-Decade and others does not fit cleanly within the masculine or feminine genders. Mac has indicated that masculine pronouns are also accepted, and this piece uses them interchangeably. The line in Hir was, probably not coincidentally, also in reference to pronouns.)

For A 24-Decade History, Mac doesn’t mess with the content itself; the content of history is radical enough. In these three decades alone, the 1/8 slice of the 24-Decade pie, American history saw the Vietnam War, the Cold War continue, the slow implementation of racial desegregation orders, Supreme Court rulings protecting the most basic of rights for many (birth control, 1965; interracial opposite-sex marriage, 1967; abortion, 1973; increased legal scrutiny of gender discrimination, 1976) and denying the most basic rights for some (states can continue to criminalize gay sex, 1986), the Stonewall riots, and the onset of the AIDS epidemic. Musically, too, these decades are among the richest — I won’t even venture a guess what all Taylor will pack in, but the choices are bountiful.

The form is what judy gleefully fucks with — emasculating the hyper-masculine, queering the oppressive, celebrating the shat upon. Remembering the forgotten and the just-as-soon-erased.

It is fitting that Mac’s epic should take that approach to history, for he has said that his theatre works were all inspired by watching the queer community refuse to be silent during some of its most torturous years, the AIDS epidemic. In a recent PBS interview, Mac said, “Their community was being strengthened because it was being torn apart. I think subconsciously, all of my theatrical work has been about that.”

More than anything else that comes to mind today, Mac’s form is using the age-old art of pageantry to command a discourse and reclaim history for the forgotten, those who the dominant, WASP, and heteronormative regime has successfully made into the “other.” (If you’re familiar with Mac’s Hir, the term “hirstory” might come to mind, when genderqueer teenager Max, frustrated with the attempts to “other” the experiences of genderqueer people, asserts, “Hirstory is not new. I’m not the new. I’m old. Just like everyone here.”)

Bringing the New-Old Pageantry

Mac’s show reinvents by injecting an over-the-top pageantry into the usual delivery method. Part of this is accomplished through Mac’s personality and banter on stage, part through the over-the-top delivery method of the undertaking itself, part by the musical reinterpretations with musical director Matt Ray, and part by the outrageous visual creations of costume designer Machine Dazzle. The result shows the history we’ve learned, but a celebration of the “othered.”

Mac has objected to being called new, an inventor, a creator — even as the show is almost guaranteed to be different than anything audiences have seen before. In some sense, though, Mac is right. Pageantry calls back to the old movements — from suffrage a century ago to the protests against indifference to AIDS and for equal legal rights — and presents a level of over-the-top that demands to be listened to. Mac’s call does judy’s foremothers proud.

I’m sure the last place you expected to end up with this piece was constitutional theory, but here we are. In his 2012 book Liberty’s Refuge: The Forgotten Freedom of Assembly, John Inazu notes that the freedom of assembly has been subsumed into freedom of speech and freedom of association (the latter of which appears nowhere in the constitution’s text) and argues that, by doing so, we have lost sight of gathering as a political act in itself in American history. “The diverse groups that have gathered throughout our nation’s history embody these three themes of assembly: the dissenting, the political, and the expressive. Theirs is the story of the forgotten freedom of assembly.” One of the early examples? Pageants, of all things, which drew attention to the cause of those society would prefer to silence. “Many group expressions are only intelligible against the lived practices that give them meaning. . . . The political significance of a women’s pageant in the 1920s would be lost without knowing why these women gathered.”

Much the same, of course, with queer assembly which, before the inventions of the Internet and the straight people marching with corporations to celebrate “gay” Pride, was the way queer people got together en masse. Pageantry was a celebration of being — in public, in groups, in a highly visible form, the same factors that so impressed upon Mac at that first AIDS march. Early on, it let queer people know they weren’t the only ones, and it let straight people know that queer numbers were swelling.

This helps, I think, contextualize what Mac is up to, and why it’s more important than a lone performer on stage. Mac is taking all of American history (240 years of it), grasping onto the little people by using the most egalitarian, cross-class and -cultural medium (popular music) as storyteller, and letting queers know this history is for them, by making a big pageant out of the whole thing.

The queering form of American history is a throwback to pageantry, and to the underutilized power of mere assembly, in which the collectivity and over-the-top of it all takes primacy over whatever is said after. An epic, garish, middle-finger-raised, We’re here, we’re queer, get used to it. How appropriate.