Review: The Fifth Wave by Lisa Every and Jenn Ruzumna. Directed by Amy Poisson. With Mari Nelson, Hugo Monday, Leah Jarvik. Produced by Macha Theatre Works at West of Lenin in Fremont. Onstage February 11, 2022 through February 27, 2022.

Actors-turned-playwriting team, Lisa Every and Jenn Ruzumna, are tackling a complex subject with their new play, The Fifth Wave. You won’t find an actual “ending” in this piece because we are all in the difficult process of figuring out our changing society and how we’re going to navigate to a better place.

The title is important, though there are differing opinions about what the fifth wave – of feminism – should actually represent. Wave 1 was voting and the suffragettes, the ability of women to be elected to political office. Wave 2 was economic power for women, the right to have their own credit, work outside the home – and be paid equally for it, be unmarried if they wished, and a crucial right to manage their own bodily reproduction. Wave 3 was an embrace of diversity, LGBTQ rights, non-binary lifestyles. Wave 4 was (is?) combating sexual assault and harassment, and working against misogyny. Many people think we are still in the fourth wave. Those who postulate we are in or are in need of a fifth wave suggest that it flips the script to focus on and empower the bottom portion of the economic scale, 70% of which is made up of women.

The subject of this play is sexual assault and harassment. It’s a big topic. We’ve seen the breakout of the “Me, Too” movement about rape. There is definite change in the air and we’ve seen powerful people brought down due to accusation, even when there is no trial and the complaint is that accusations mean there is no “due process.”

While “due process” might be a good remedy in some cases, the point is more that women are harassed and attacked daily in large and small ways that do not stack up to an easily-charged court case. We all know this, and we all know that the burden of that is generally on women to “be careful” and to be aware of their surroundings and to watch their drinks carefully in places that someone could slip drugs into them. Or we know to put keys between our fingers when we walk down the street alone, especially at night.

The playwrights focus on Maxx Cheevie, a college professor in what seems like a small town college. It’s been 25 years since she was brutally attacked and assaulted as a young college woman. At that time, her young self was so brave and self-aware that she returned the very next day to the scene of the assault, in the condition she was left (naked and with an attack-shaved head) to stand naked again and proclaim that she was taking back her nakedness and her femininity and her sexuality.

Presumably, it was at minimum audio-taped. She was celebrated for her courage. The speech was cemented into the culture and the memories of the college students. So much so that she is to be feted at a special ceremony of remembrance to acknowledge her impact on the ability of women to regain their power. Also, she went on to become a professor of women’s studies or sexuality or something similar to teach about the change that needed to come.

Then there is an “incident” with a male and female student. No one knows quite what happened, but they believe she was hurt and that he did it. They want action, they want consequences, and they don’t want to wait for an investigation. While we don’t meet or see the allegedly assaulted woman, we do meet the young man, though we don’t learn much about him or the incident.

Maxx, however, becomes the center of protesting young women who want her to step up and denounce his continued presence on campus and to support the woman. But Maxx is conflicted and finds herself roiled up with emotions or memories she thought long-amended.

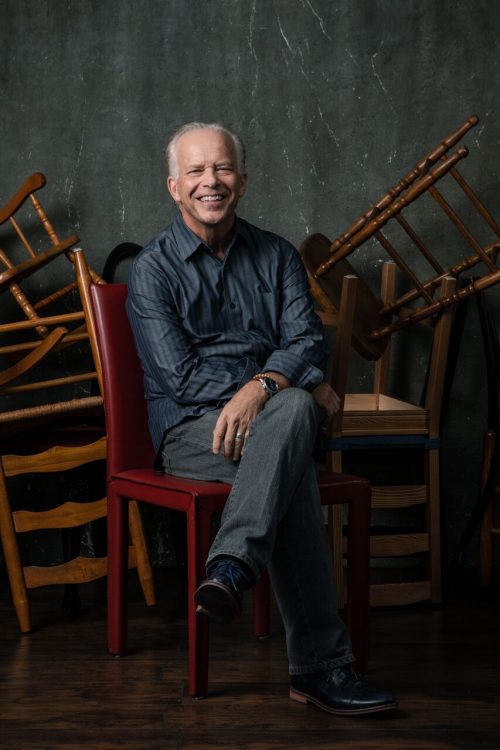

Director Amy Poisson has been supremely fortunate to have cast and kept (for two covid years) one of our areas top-notch talents, Mari Nelson, as Maxx. Nelson lends credibility to any role she plays and could make the encyclopedia sound dramatic. Then, Hugo Munday is cast as her husband, Jo, and since they are a long-married couple playing a long-married couple, this adds a subtle level of unconscious comfort to their relationship.

Maxx and Jo have a daughter, Jessie (Leah Jarvik). There are a group of 5 actors named “Fury” and they function as a Greek Chorus and also become the students of the college and in Maxx’s classroom.

The production, helmed by Amy Poisson, is sharp and specific. Everyone knows exactly what they should be doing. The set by Parmida Ziaei is sleek, super-looking, and minimal. Location changes might be instantly different by moving some chairs and, personally, I appreciate that “less being more” effect. Dani Norberg’s lights and Lisa Finkral’s sound all combine to make a satisfying environment.

The script has a less well-formed presence. It could be refined a bit more (not from a length point of view, but from intention). In this script, the young man and young woman are already in a romantic relationship and were apparently drinking. To an extent, that then makes the conversations much less clear about what could have gone wrong that night. It’s not like the subject matter specifies how difficult date rape is to determine, for instance, or helps reveal the delineations needed for young people to learn how consent should work (if that was any of the intent here).

Because of that, the polemic is muddier. The stakes for the characters and what they “want” could be clearer. The Furies lend some tension when they are not college students. But it’s unclear why one and only one of them has zero words in the script. The intention there seems more “meta” and hard to determine, yet she steals the scene sometimes with her stately movements.

It’s definitely worth a look, if you have a chance this next weekend before it closes. Whether it completes the whole journey, it’s a look inside ourselves as we struggle to become “better” at giving women room to be entirely themselves. We might be in a fourth wave and need a fifth one, or might be in a fifth one that we haven’t clearly defined, but there is no question that society is convulsing toward recognizing half the world population as being as important as the half that has reigned supreme.