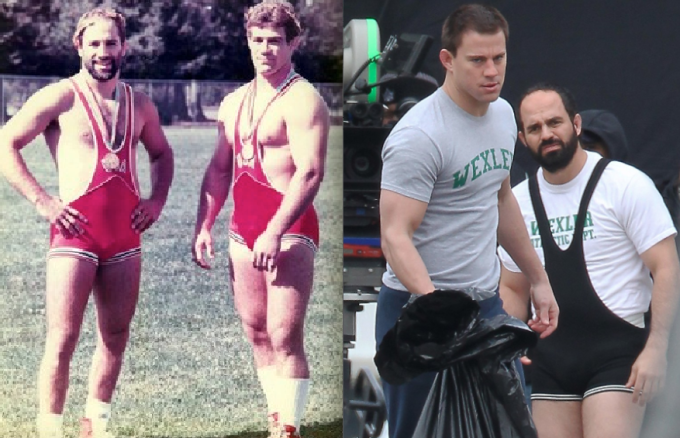

The Schultz Brothers, Dave and Mark, and the actors who portrayed them in “Foxcatcher”, Channing Tatum (Mark) and Mark Ruffalo (Dave).

What is gay cinema? It seems like a simple question, but try to give it a simple, accurate answer. It seems before we can begin to understand what constitutes gay cinema, we must understand what constitutes gayness, and that is no small undertaking.

Porn is an easy baseline, if we wanted to jump right in to the shallow end. The next most obvious category comprises films that show gay characters in gay-themed scenarios. After that, gay cinema becomes difficult to define. What about films with no overtly gay content, but that inspire us or connect with us anyway? What about films with characters who are ostensibly straight but may be coded as gay via behavior or context?

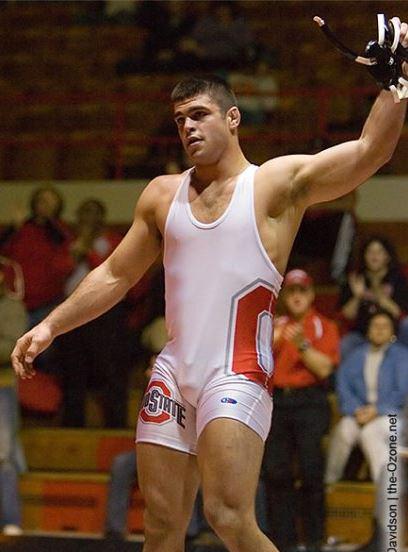

A recent film that might belong to that last group is Foxcatcher, a 2014 effort directed by Bennett Miller of Capote and Moneyball fame. Foxcatcher combines sports and ambiguous attraction as it tells the true story of Mark and Dave Schultz, two Olympic Champion wrestlers who trained under a wealthy patron named John DuPont. It also may be about the trouble that can develop when boys fall in and out of love, but you won’t read that on the poster.

None of the characters in Foxcatcher are overtly or historically gay. Two of the three main characters are brothers. Yet one of those brothers, Mark Schultz, once objected in the press to the film’s homosexual undertones. From where do these undertones emerge? Are they enough to qualify Foxcatcher as gay cinema? Perhaps we need a new subset: gay (undertone) cinema.

Foxcatcher explores the complexities and nuances of male relationships, in part through the action and metaphor of wrestling. Men lock eyes, (hearts?) and arms as they engage in the exploratory micro-aggressions of their sport, swaying forehead-to-forehead, testing each other with little slaps; searching for weakness, vulnerability, and instability in the sculpted bodies of their opposites. Foxcatcher uses its relatively few wrestling scenes with purpose and precision. When Mark is at his lowest point in competition, note how he is depicted: with his ankles in the air.

The body is often central to gay male cinema. Foxcatcher is no mere beefcake picture, but the body does matter here. Posture and movement are key. Wrestlers prowl hunched and simian under the weight of their training, hugging and grappling each other to please their “coach,” John DuPont, who by contrast negotiates space like a soft automaton, a disconnected CEO among man-beast employees / sex objects, sometimes insinuating himself into awkward congress with his hirelings. Proximics are telling here as well: characters are sometimes separated by the width of a leotard skin, and other times by the wide, cold expanse of a mostly featureless gymnasium. The physical space between characters often mirrors the emotional.

The body is often central to gay male cinema. Foxcatcher is no mere beefcake picture, but the body does matter here. Posture and movement are key. Wrestlers prowl hunched and simian under the weight of their training, hugging and grappling each other to please their “coach,” John DuPont, who by contrast negotiates space like a soft automaton, a disconnected CEO among man-beast employees / sex objects, sometimes insinuating himself into awkward congress with his hirelings. Proximics are telling here as well: characters are sometimes separated by the width of a leotard skin, and other times by the wide, cold expanse of a mostly featureless gymnasium. The physical space between characters often mirrors the emotional.

Dig deeper and you’ll find that Foxcatcher is a modern blend of Pygmalion and Hellenistic paiderastia. Here the ancient relationship of old erastes and young eremenos is reconstructed. John DuPont lacks the vim to express his power and wealth through his own body, so he finances a kind of Grecian university where Mark trains and develops. Mark is John’s golden-brown champion, his ticket to a second youth. John gives him gifts and teaches him how to behave in the rarefied environments of the super-rich. You might detect shades of Behind the Candelabra in Mark’s transformation from dull, blue-collared jock to frost-haired, coke-snorting trophy. At any rate, need services need and all begins well, but of course the situation degrades. John is no mentor, but rather an ineffective dabbler-cum-fanboy. Mark plays his role closer to type, initially succumbing to John’s dull vampiric spells before breaking away. These characters suffer deep need and repression, after all — a familiar combination in gay cinema.

While explicit sex is absent in Foxcatcher, repression of desire is not. It is in that repression where gayness is perhaps most powerfully and painfully insinuated. John DuPont’s stable of wrestlers are equated with his mother’s stable of horses, indicating a kind of dehumanization inherent in his efforts. What are his wrestlers to him but livestock, trained to bring glory to their master? But that is only illusion. John might emulate his overbearing mother’s methods, but his connection to his gladiators is deeply personal, and rooted in secret, long-held desires. He wants to be one of the boys, to roll around with them on their sweaty mats. But he can’t allow it, because his mother won’t allow it. He must disguise his desire as a business venture, thus hiding it from his disapproving mother in a dynamic that clearly echoes closeted homosexuality. For DuPont, “the love that dare not speak its name” is very real.

One could argue that all of the above is invention, but it is a worthy exercise to consider what makes filmic same-sex interactions gay. Is sexuality woven however lightly into every possible cloth? Is it coterminous with humanity itself, its relationship to all other behaviors merely hidden or suppressed through mores, decorum, and protocol? Is this threat of potential homo universality one origin of violent opposition to gayness? Is cinema at its most gay when it asks these questions, thereby troubling dominant, heteronormative paradigms? Foxcatcher welcomes but ultimately complicates discussion about its own classification as gay cinema, and that is one of its many strengths. Its characters are as concrete and liquid as the people who watch them.

The next question is this: If Foxcatcher qualifies as gay cinema, or as gay (undertone) cinema, how do we feel about it as such? It might be, in some strange way, this decade’s Brokeback Mountain, but that is a topic for another conversation. For now, I’m calling Foxcatcher a top contender for 2014’s best gay (undertone) film — whatever that means.