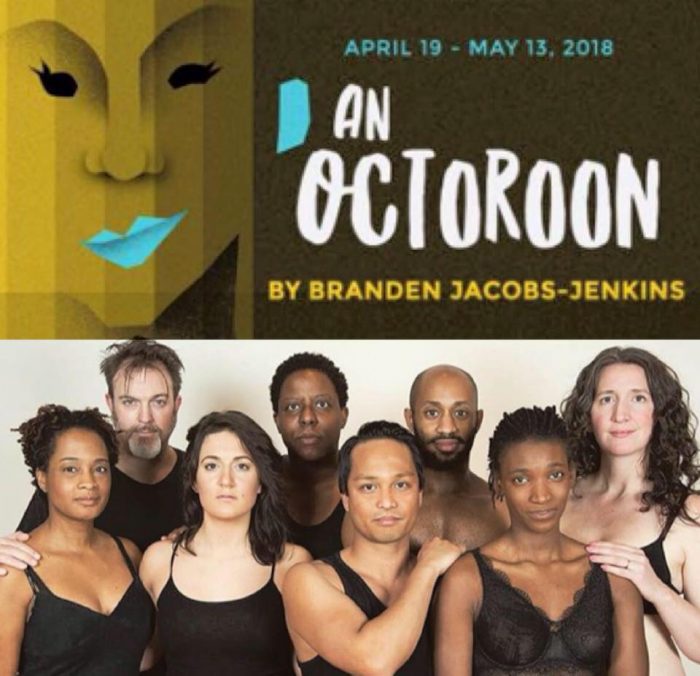

The astonishingly brilliant cast of ArtsWest Playhouse’s production of “An Octoroon” that examines American racial issues through the lens of a 160 year old play. From left to right: Jose Abaoag, Lamar Legend and Heather Persinger.

Review: An Octoroon by Branden Jacobs-Jenkins. Produced by ArtsWest Playhouse & Gallery. Directed by Brandon J. Simmons. Scenic Design by Julia Hayes Welch. Costume Design by Doris Black. Lighting Design by Mathew Webb. Sound Design by Matt Starritt. Properties Design by Andrea Spraycar. With Lamar Legend, Mike Dooly, Jose Abaoag, Jessi Little, Heather Persinger, Dedra D. Woods, Jéhan Òsanyìn, Jazmye Waters. Onstage from April 19, 2018 to May 13 2018 at ArtsWest Playhouse/West Seattle.

While “Oscar Wao” is a one man show, (read my review of Part 1 of “Powerful New Plays Demand Your Attention” over HERE) albeit a complex and deeply rewarding one that examines Dominican American culture, ArtsWest Playhouse is also staging a similar kind of complex theater but one with a far larger cast and even more complicated themes on American racial/cultural identities.

It’s their astonishing powerful production of noted young playwright Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’ AN OCTOROON, his adaptation of 19th century playwright/producer Dion Boucicault’s The Octoroon (1859), which was an 1859 adaptation of a popular anti-slavery novel of the same name. Like its predecessor the more famous Uncle Tom’s Cabin, these melodramatic stories, albeit works that were anti-slavery in tone and sympathetic to the plight of enslaved African-Americans, were also profoundly racist and detrimental to African-Americans for creating and establishing damaging stereotypical and racist characterizations of black people. The “Uncle Tom” and “Mammy” caricatures became a part of popular culture for the next century and more before the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s began to chip away at these stereotypes and branded them as unacceptable.

Branden Jacobs-Jenkins uses The Octoroon (1859) as the basis and framework for his adaptation but makes it clear this is very much a modern take on 19th century theatrical norms…what was acceptable in that period is certainly not so now. Jacobs-Jenkins opens his version with a prologue with a modern young black actor standing in for the playwright himself and onstage deliberating about the actual production we are witnessing…the difficulty of producing a modern adaptation of The Octoroon (1859). In this meta-reality, all the white male actors have quit, so “BJJ” the stand-in for our playwright decides he will have to don “whiteface” to play the white male roles. And, in a further meta-twist, the “ghost” of the original 19th century playwright Dion Boucicault becomes an character as well, and “BJJ” dragoons him to don “redface” to play Native American roles and “The Assistant” who is Asian-American, into putting on “blackface” to portray black male characters.

Yeah…that’s a lot of scary artistic choices to make in the 21st Century; not advisable for just anyone to attempt to pull this off, but the brazenness of Jacobs-Jenkins’ adaptation is so well handled and the concept so smart, that it makes not only powerful statements on racial issues but how we have portrayed race in the past as well as in the present. The shock value of having a Black man, a White man and an Asian man all wearing offensive approximations of other cultures is daring and effective as commentary on race but also on the art of making theater and popular culture. An Octoroon isn’t just about discussing issues OF race but it’s also about raising issues on the creation of ART…on how we have made theater over the last 160 years. Which, as a theater geek, is fascinating as hell.

From that prologue we immediately break into the actual melodramatic plot of The Octoroon (1859), a complicated multi layered romantic drama with a huge cast of characters but all centering on the “Terrebonne Plantation” in the Deep South and presumably on the Mississippi River since a river boat figures into the plot. Our vapid but dashing young white hero George (but played by the African American actor who is playing the playwright “BJJ” in whiteface as “George”…yes, there’s a lot of layers here) has returned home to claim his inheritance of Terrebonne only to discover that the plantation is in financial peril and in danger of being sold to creditors which of course means… selling all of the slaves.

Slaves = Property.

A debt owed to the estate would solve George/Terrebonne’s money woes but the evil white overseer M’Closky (also played by the same actor playing George…yes, lots of quick changes here) wants Terrebonne for himself and manages to steal the letter containing the promised payment that would save the estate. In the process, M’Closky kills the young male slave Paul (played by the Asian-American assistant in blackface) and frames the death on a local Native American named Wahnotee played by the white actor in redface.

Got all that?

There’s also several female characters but they’re all played by the actresses of the appropriate race, (mostly) meaning white actresses play white roles; black actresses play black roles, in this case a trio of slaves (two house slaves, of higher station and a field slave) who comment on much of the action of the play but…humorously. Because that is one of the delights of this play which IS billed as comedic; it IS frequently very funny, though the audience I saw the show with seemed skittish about laughing at things that are MEANT to be funny. The humor with the female slave characters is mostly rooted in the fact they portray their roles within a modern context..as young modern urban woman sitting around having a good juicy gossip about all the bullshit going on at work. But, when white characters enter the scene, they immediately revert to submissive/passive stereotype slave behavior patterns…which isn’t funny.

There’s also a young white woman from a neighboring plantation who is determined to marry George (which is also a marriage that could help solve Terrebonne’s money woes) but George is infatuated with a lovely young but poor relation of their family named Zoe who is, in actuality…AN OCTOROON AND THE TITLE CHARACTER OF THE PLAY!!!

Cue dramatic chord of music.

And, of course this is a problem. Under the one drop rule, anyone with just one degree of “black” blood in them is therefore not “white” and not able to marry or mate with “pure blood” white people, due to laws of miscegenation. (An “octoroon” is one eighth black meaning they have one great grandparent who is African. A quadroon was one quarter black, meaning one grandparent was and someone with one parent who is black and one white would be “mulatto”…yes, they had a bloody ridiculous system of tagging people.)

So, George is forbidden to love/marry Zoe and M’Closkey wants her for his bed so after killing the black child, stealing the money that would save Terrebonne, he announces he plans to buy Zoe who is still technically a slave and property of Terrebonne since her white father forgot to emancipate her.

By now we’re up to Act III (19th century melodramas were long!) which back in the day would have featured a big spectacle of theater (George fighting M’Closkey after everyone discovers M’Closkey is a murderous villain and then the river boat explodes and all hell breaks out) but An Octoroon features a different kind of shocking theater trick: it displays an actual photo of a real racist act. And, this is one of the astounding features of An Octoroon as it shifts back and forth between the fiction/larger than life fantasy of the original story with moments of modern reality start to peek through…actors break character to comment on the action or, in some cases, actors expressing disgust at the actions going on in the play.

And, that’s the odd thing about this play. It’s a fascinating and sharply clever commentary and bitter expose of racism, both past and present…but, it also gives audiences the experience of witnessing a long dead brand of theater making…both the good and the bad. The rich florid melodrama of “old timey” plays is seldom performed anymore; it’s out of style and out of touch (and usually sexist and/or racist), but it’s also a fascinating and compelling piece of drama. Dion Boucicault was a master of telling stories so despite all the horrifying racist caricatures in this kind of material, it’s still compelling drama. An Octoroon is a long show, over two and a half hours but it doesn’t feel long. At the heart of it, it’s lush and ridiculous soap opera and you do become invested in the characters. Which does make you feel kind of…dirty for being pulled into it. It’s like watching the classic and much beloved (by some) 1939 film Gone With The Wind and admiring the gorgeous lush film making and story telling but seeing it through 21st century eyes, you can’t not be appalled by the presentations of the African-American characters.

And, I’ve spent a lot of time on the plot and background of the play itself, its inherent…smartness…but the success of this production is also due to Brandon J. Simmons’ equally smart direction. This is a big show with a lot of characters and plots and multiple layers of meaning and subtext and it’s all laid out with this clear and concise and choreographed staging of these terrific actors. It’s a superb job of direction. (Read our interview with Mr. Simmons over HERE.)

Oh, and, that’s the other thing we need to talk about: the superb ensemble of actors and the fact that Seattle has had several shows that are so well cast and performed. Seattle theater is on a hot streak of late with theater companies finding strong scripts that feature a strong ensemble of characters and then finding JUST the right actors to play these roles. Right now, as of this writing, there are several local productions with PERFECTLY integrated casts of actors all working in some sort of magic merging of talent. (The other shows: MAP’s The Year of the Rooster and ACT’s The Wolves both with terrific ensembles).

An Octoroon has eight impeccably cast actors who are all just so damn good at playing all the various layers they are required to play including these insanely larger than life 19th century characters which is very tough to pull off…people think “big hammy” roles are easy to play but the truth is, “big hammy” roles are easy to BADLY play and very difficult to portray with sincerity and depth and every single one of these actors pulls it off.

All eight are outstanding but for different reasons because they have different kinds/layers of roles to play within the context of the play as well as different styles of acting to present. The actors of color, are all playing the material AS actors of color portraying these stereotyped characters…there are obvious multiple layers expressing this duality. It’s actually more than a duality of acting…it’s real person “Lamar Legend” playing an approximation of the playwright, Branden Jacobs-Jenkins who plays these two different characters, one “good” and one “bad” but both artificial creations of the highest theatricality. Playing that many layers isn’t easy but he does it and the result is a bravura performance from Mr. Legend.

The other two men, Mike Dooly and Jose Abaoag, who are, remember, in “red” and “black” face respectively have to play similar layers as well, and both are superb. Mr. Abaoag has the added weight of having to present, as an Asian-American artist, the disgust of playing African-American caricatures that are patently offensive, but managing to do with great commitment and bravado and yes, even humor and charm.

The women are a different story to a certain degree because the African-American actresses playing the slave roles aren’t in offensive make-ups, though their roles also require those sometimes subtle/sometimes not shifts in duality from submissive chattel to frankly modern and empowered. Dedra D. Woods, Jéhan Òsanyìn, and Jazmye Waters are just sublimely great in these roles.

As for the two white identified actresses, Jessi Little and Heather Persinger, they present an entirely different kind of acting because they’re not playing those same kinds of duality…they’re just brilliantly interpreting 19th century acting styles without any subtext of them being anything or anyone other than these larger than life characters. And, as I stated earlier, GOOD “big” acting is difficult to pull off but both Ms Little and Ms Persinger are very committed to the roles and how they have to be portrayed.

This is a longer than it should be ramble, but great impassioned theater needs to be passionately discussed. I haven’t said anything about the design elements, but they are, as usually is the case with ArtsWest, well done. Julia Hayes Welch’s scenic design and Matthew Webb’s lighting and Matt Starritt’s sound and Andrea Spraycar’s props and very much so Doris Black’s on the mark costumes are all huge assets for this production.

In case you haven’t been paying attention, I very, very much recommend this excellent piece of provocative theater making. It’s not an easy night of theater, but it’s a profoundly moving and smart one. An Octoroon is a theater highlight for the year and kudos to the entire team behind it.