Perfect for your First Thursday plans, make it a point to see Double Exposure this week — closing this weekend at the Seattle Art Museum — and In This Imperfect Present Moment, which just opened.

Double Exposure (Closes 9/9)

In photography-speak, a double exposure refers to exposing a single print twice, each with a different negative, resulting in the layering of two images on one print. Of course, not all double exposures are created equally — and the two images often get unequal play. Such is the case here, with its namesake exhibit.

The theory of SAM’s Double Exposure exhibit is to layer different artists on the work of an early one, in order to create a more robust picture of Native American imagery, past and present. It therefore brings together the historical work of photographer Edward S. Curtis, a white man, with three modern Native American artists: Marianne Nicolson (multimedia), Tracy Rector (filmmaker), and Will Wilson (photographer).

The exhibit uses as its anchor the work of Curtis, an early photographer who centered his work around capturing images of Native Americans, many of them portrait-style, in the early 20th Century. Curtis amassed an enormous body of work, and his prints created the rare lasting images of Native Americans around that time. (I was unfamiliar with him before seeing this exhibit, but recognized some of his work.) Curtis is criticized for showing Native Americans through a blurred lens, by posing his subjects and adorning them, even with props he brought along rather than capturing their authentic appearances.

Accompanying the problems are many positives. For one, the images create a visual record of Native peoples that would otherwise not exist, and for that reason his images are invaluable as research tools and helping memorialize the many tribes he worked among. That record is an extensive one: 150 images are on display at SAM, but Curtis took many, many more, and published 20 volumes of pictures. And the images themselves are of phenomenal quality — well thought-out setting and lighting, a captivating subject, and notable sharpness. That these were taken at a time when capturing one image meant lugging around heavy gear and plates, makes the quality and breadth all the more incredible.

The main problem I encountered with the exhibit is there are three other artists, Native artists, yet the lens of Curtis remains the focus, by the sheer volume of his prints throughout the galleries. Nevertheless, the three contemporary Native artists featured mark a welcome change from the traditional display of well-known, white artists without comment.

And it is the contemporary art that greets you at the door. Visitors can’t help but gravitate toward the large, lit-up, shadow-throwing arch by artist Marianne Nicolson, located at the exhibit entrance. Reminiscent of the Peace Arch at the U.S.-Canada border while full of Native American imagery, the structure speaks to the negotiations between the two countries about the use of the Columbia River and the impact of its changing landscape. A linguist, Nicolson also created a “sound shower,” which rains down recordings of welcome as visitors enter the exhibit.

Filmmaker Tracy Rector’s work forms the other bookend of the exhibit with a film installation at the end that surrounds viewers, with films playing on big screens on either side, handcrafted wooden benches, and troughs of shells. On one side is a series of nature scenes; on the other, a documentary about a Native woman who dives for geoducks, Pacific Northwest delicacies that are sold around the world.

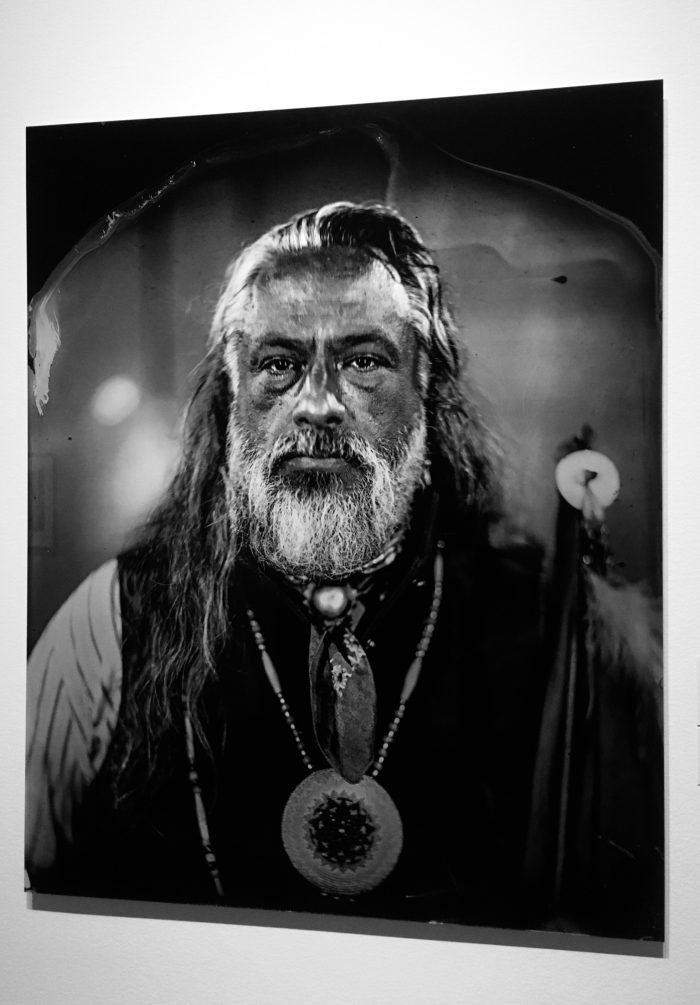

But the contemporary artist whose work most permeates the exhibit is photographer Will Wilson, whose larger-than-life tintypes are displayed throughout. There are only perhaps a dozen of them — paling in comparison, in quantity, to the Curtis images displayed around them — but are enormous, printed in bold inks, their subjects commanding attention. They stand out.

Some of the subjects of Wilson’s portraits are local artists who will be familiar to some viewers, including fellow artists in the exhibit; Two-Spirit poet-activist Storme Webber; artist and ritualist Timothy White Eagle (an artist-in-residence at On the Boards, whose show will go up later in the 2018-19 season); and more. It’s powerful to see them conveyed in this exhibit with such stature. In that respect, Wilson’s portraits call to mind the current exhibit at Northwest African American Museum (NAAM) — Everyday Black, up through September 30 — which features contemporary portraits by Jessica Rycheal and Zorn B. Taylor, whose stunning, larger-than-life portraits serve as windows into personal stories, many of them also of local artists.

A significant part of Wilson’s portraits, however, is an aspect most viewers appeared not to notice: the added features that allow the portraits to come alive with an app called Layar. It’s an easy process: you download the app, point it at the feature-enabled portrait (noted near the captions as being Layar-enabled), click to scan, and suddenly you’re in the middle of an interview, a dance, a poem, an invocation. I was able to download the thing and scan the photos fairly quickly, then watch the videos at home — though if I’d had more time, it may have been more satisfying to watch them out in the lobby, then come back through and see the exhibit through new eyes. Although there were plenty of signs and instructions around the exhibit for operating the app, I saw no one in the exhibit actually scanning them — and it’s unfortunate that more emphasis wasn’t placed on the value of doing so, since it ended up being content integral to the experience. (I do empathize with those who skipped that aspect, though — I’m not an app or a bonus-features person, and if I wasn’t reviewing it I probably would have skipped it, too. I’m glad I didn’t.)

In This Imperfect Present Moment (Through 6/16/2019)

Another exhibit, called In This Imperfect Present Moment just opened (in the third-floor galleries), and will stay until next summer — but feels relevant to the exploding world around us and necessary to see now.

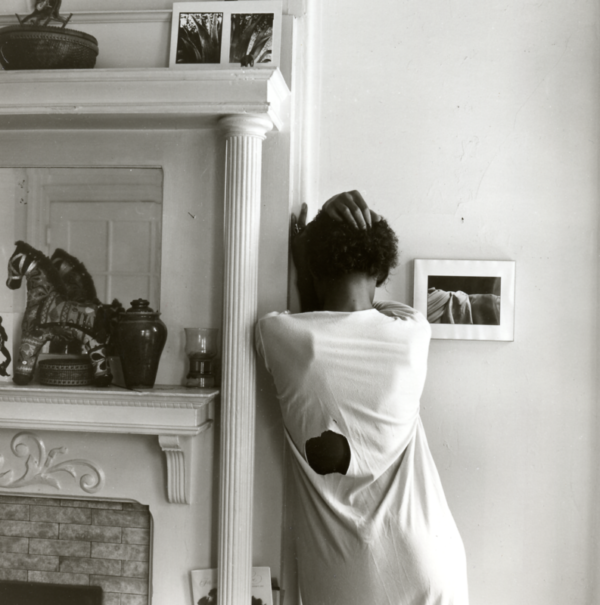

It’s a diverse collection, both in subject and medium, and flows together primarily in its disjunction: a sequined bust sits a few feet from a portrait of a mother and her children, a beautiful family caught in a quiet, posed moment together, who we’ll learn from the title and caption have since died from AIDS.

Several feet down, a group of photos from a large body of work by twin brothers shows the contrasts Muslims face in modern societies. The first of the photos came alive to me: this is what adults would look like in the playgrounds of their childhood if they cast inhibitions aside and truly embodies the wild and innocent spirit of that age. It’s funny; but it feels right, and freeing.

Other pieces poke fun at global dictators and financial systems of oppression; portray work and poverty; and speak to personal identity and cultural identities. At the exhibit’s entrance is a stunning piece by Amy Sherald, who was commissioned to paint Michelle Obama’s portrait. There are 20-some pieces in all, by 15 artists from around the world.

The common thread among the works comes from their complex layers. The premise is described in a quote by Toyin Ojih Odutola, whose portrait is included in the show and supplies the title of the exhibition, who focuses on “the understated in art: moments that can be quickly passed over but are complex and layered.” Art mimicking life.

And More (Permanent Exhibits)

Either of these exhibits alone would be worth the trip, but it doesn’t have to be a one-and-done at SAM, with its several levels and many nooks. My personal favorite is right next to the Lawrence galleries, with windows overlooking Union Street (and Target and, today, a dead pigeon). This particular nook is usually quiet, save the white noise of a video (this one a 2018 called “Dragging a Painting”) while a 1978 B&W dance video plays silently next to it. Also there, a giant meta painting of paint, and a giant ball of barbed wire with a “please do not touch” sign. Good call.

Other exhibits, permanent and long-term temporary, abound throughout the museum, and cover a lot of ground: from Pacific Northwest to Europe, Africa, Asia, and more; from Imperial China (“Pure Amusements”) to contemporary American (“Big Picture”).

Re-entry is allowed, so if you need a break for a snack, a coffee, or a tray of truffles at nearby Fran’s, go wild. And if you come on First Thursday, you’ll be just a short walk from the galleries in the south end of Downtown and throughout Pioneer Square, for exploring before or after.

Seattle Art Museum is located in Downtown Seattle, at 1300 1st Ave. (main entrance at 1st & Union). Hours: 10am-5pm most days; closed Tuesdays; open late (until 9) on Thursdays. Admission is $24.95. First Thursdays, get half-price admission for special exhibit (Double Exposure) or free admission for everything else, including In This Imperfect Present Moment.