In the life of a film critic, you end up seeing a lot of films. I myself have seen over 150 so far this year. In between all the mediocre and passable slop, you’ll find the one rare gem that makes it all worth it – the beautiful, innovative, nearly-flawless masterpiece that you’ll carry with you for years after. Then there’s the breed of film that’s even more rare – the kind that you undoubtedly dislike, but challenges you in such a way that also ends up lasting beyond the viewing. To me, Joey Kuhn’s Those People is one of the latter.

The film (which has its final SIFF screening on June 6) stars newcomer Jonathan Gordon as Charlie, a young Manhattan art student whose best friend and lifelong crush Sebastian (Jason Ralph), is caught up in a complicated and seemingly massive financial scandal involving his father’s company. Meanwhile, Charlie attempts to move past his feelings for Sebastian with the charming pianist Tim (Haaz Sleiman). The main conflict in the film comes from Charlie’s battling feelings between the two.

The film felt incredibly problematic to me due to its depiction of wealth and upper-class life. I felt as though the film was manipulating me to feel sympathy for the spoiled and wealthy Sebastian, while callously ignoring those who are truly struggling as a result of his father’s actions. It was as if the film brought up important issues like wealth inequality and financial corruption, while somehow completely ignoring the victims. At the same time, I couldn’t help feeling the film was skillfully made. Those People has strong characters, solid acting and a high production value.

Meanwhile, our own Ryan Crawford had a completely different opinion. According to him, “Those People positions itself in the vanguard of the new LGBT film wave as an instant classic about loyalty, forgiveness, self-nurturing, and accepting love even when you don’t feel you deserve it.” Well then.

How can two critics have such polar opposite opinions about the same film? Is Those People trying to force sympathy for rich criminals? I sat down for a conversation with Joey Kuhn, the film’s director, to find out.

Jeff Coté: To start, I was wondering if you could talk about what your purpose for making the film was.

Joey Kuhn: I was ready to make my first feature and I knew that I wanted to tell a story about a gay romance where the main character comes of age, kind of finding out who he was on his own. I look to my own life for inspiration and the love story I knew best was this five-year unrequited love I had for my gay best friend in college and shortly thereafter. So I used that inspiration as the basis for the main friendship in the film between Charlie and Sebastian. I think a lot of my reasoning for doing the story was to work through it myself, because I was very much in the thick of it when I started writing the script. I was still very much in love with him. So I had a feeling if I wrote it and acted as my own therapist and worked through those issues and then did the filming, I could finally move past him. Which I was able to do.

I also really set out to make a film that I could love, that I knew people like me and the audience I was trying to go after would love. I had never seen a grand, New York sweeping gay romance, so I wanted to make one for me and other people that I knew would enjoy it. That’s why I set it against the larger backdrop of the Upper East Side, where I could kind of deal with bigger themes like fathers and sons and unrequited love and deal with it in a more dramatic way. I knew I didn’t want it to be this dramatic, “slice of life” Brooklyn film that you see a lot. I wanted to go for bigger emotions and not shy away from that.

JC: Right. I know the whole term of “queer cinema” kind of has a negative vibe to it sometimes. You know, as queer people searching for films, there’s a lot of…

JK: There’s a lot of crap out there.

JC: Yeah. For sure.

JK: You know, I think queer cinema is incredibly important and there are a lot of amazing films out there. It’s just that I think there’s a higher volume of not as good content. I find that the production value is usually a lot lower, that strangely enough you find a lot of more stereotypical characters in content being made by LGBT people. But again, there are so many wonderful films out there. I wouldn’t take this giant paintbrush and say all queer films are terrible. I would never say that. But it’s true that it’s extremely hard, like you said, for our community to find stories that resonate as authentic and true and we can actually see ourselves in them.

JC: Definitely. We actually had one of our other writers review your film, I don’t know if you saw it.

JK: I did. It was such a wonderful review!

JC: Yeah, he loved it and I think a big part of his reasoning, from what I could see, was that your film is a bit different in that it’s not a coming out story. It’s a film that’s exploring other things that human beings experience. Imagine that.

JK: Well, you know, I was very deliberate in the way I was telling the story because I wanted it to be universal. I wanted it to just be about people. As excited as I am to make this film for the gay audiences, I knew I wanted to break out the LGBT film festival ghetto and– Well, I guess ghetto’s not a great way to put it.

But a lot of times these gay films become super niche and only its core audience sees them. I wanted a larger audience to see it because the best way to get straight people, or people who don’t know gay people in their own lives, to start thinking about gay people and gay relationships as equally valid as their own is to just show relationships the way they are, how human and universal they are. I didn’t want to get super political in terms of LGBT politics with it. I just wanted to tell a human story and then let that speak for itself.

JC: I definitely think you’ve done that. You’ve created a film that is something that people can relate to on the level of any other film. It’s very professionally made and the acting is very good. I remember while I was watching it, I saw Haaz Sleiman and I was very pleasantly surprised. I remember seeing him in The Visitor and I thought he was great. I actually thought his performance in your film went beyond that. It’s a very solid role and I think you were able to direct the actors very well.

JK: Thanks. You know, Haaz is really wonderful to work with and he’s such a pro. He has this amazing ability to, as soon as the camera goes up in front of him, he just kind of settles into this zone and knows exactly how to act for the camera. He never goes too big, he is just very real on screen and I loved working with him. He’s a very talented guy.

JC: That’s good to hear. In hearing people’s reactions, what are some of the things you’ve heard people saying about the film?

JK: The biggest thing that we hear is that gay or straight, everyone has a “Sebastian.” People love to relay their own stories of the best friend they had been in love with for years. So that’s been really cool. I mean, that’s what you want to be able to do with films, right? To have other people relate to them and see themselves in the film. I just wanted to make a film that people feel passionate about. We’ve heard that visually it looks much different than what they’ve seen in other gay films and that’s been very rewarding too, because the whole team really set out to make a very beautiful film. I wanted to create this world that you just wanted to dive into and live in. The visuals are just very important to me.

JC: I think it’s relatable on a human level for sure. You can definitely relate to the characters’ emotions. However, I felt that the narrative wasn’t really relatable for me. I was a little confused by your intent with the white collar crime element, with Sebastian’s father.

JK: Did it turn you off? Is that why you didn’t enjoy it?

JC: Maybe in the end it turned me off a little bit. I think the source of the confusion was that I didn’t quite understand what your intent was.

JK: Well, I like movies that have a larger sociopolitical backdrop and I grew up in New York. A little bit before I started writing the script, the fallout from the Bernie Madoff scandal was going on. I knew a lot of people who lost money to Bernie Madoff and in fact, NYU itself lost something like a third of its endowment. So it affected not only a lot of people I knew in New York, but the whole student body. While this was going on, I was really drawn to his son Mark Madoff, who killed himself a year after his father went to prison.

Bernard Madoff leaving US Federal Court after a hearing regarding his bail. (c/o Timothy A. Clary/AFP/Getty Images)

I thought that was a really interesting character study to bring into the film, this guy whose life is ruined for something he presumably didn’t do. And so that became the jumping off point for Sebastian, because I didn’t want him to be the main character. I didn’t want the audience to necessarily have to sympathize or align themselves with this guy who brings this pre-existing baggage because of all the terrible Ponzi schemes that already go on everywhere. People bring this baggage with them to this film and to this character. So I wanted to explore this character through the eyes of someone who loved him the most.

I myself am fascinated by characters who are difficult. I think about Dickie Greenleaf in The Talented Mr. Ripley. Dickie is an asshole who is this golden boy who loves attention, but you find yourself drawn to him because he’s beautiful and he’s charming. So that’s why I explored it. But I just wanted it to be a backdrop. When I first started writing the script, it used to take place during the trial and Sebastian had to testify against his father.

JC: So what made you change your mind about that component?

JK: I found that was the part of the story that was the least interesting to me. I didn’t feel like I wanted to explore the trial or all the legal stuff surrounding it. For me, what became the most interesting part was the central friendship between Charlie and Sebastian. But I kept that connection to the financial scandal because I felt that that it raised all the stakes. If Charlie and Sebastian had just been two regular guys in New York, it would have still been a lovely, human story. I just wanted to make it grander and put Sebastian in this predicament, in this point in his life when everything is falling apart in a major, exaggerated way.

JC: So in the end, is Sebastian complicit in the crime? It seemed like he did know about what was going on and was in some way guilty for that.

JK: He is. He feels a lot of guilt because of what he knew and as he says in the film, he knew what his father was doing and he didn’t stop it. He didn’t feel like he could stop it. That’s the guilt that’s underlying all his actions in the film. In the end, I knew I wanted Sebastian to not have done anything technically, legally wrong, but feel this guilt because he felt like he could have done more. It’s like the innocent bystander thing. Do you call the police when you see something horrible happening or do you just walk along your way and hope that someone else deals with it? I wanted him to have this question of identity. Another reason why I kept the financial scandal a part of it was that I knew everyone was dealing with father issues in the movie, all the main gay characters.

Charlie’s father left when he was young without saying goodbye and he’s constantly had a lot of issues with that. Tim talks about his father who was a bit of an alcoholic and was a bit abusive toward his mother. Sebastian has this father whom his whole life he’s thought was this perfect grand guy, the way a lot of people grow up thinking about their fathers. And then once he realizes his father is this kind of awful person, he has to re-examine his own identity too and take his father off this pedestal.

So was it that you couldn’t relate to Sebastian that distanced you from the film? What did you think the film was saying with that character?

JC: I actually felt kind of alienated from the film because of the depiction of what Sebastian is going through, with the paparazzi bombarding him and always staying inside, becoming an invalid. It felt a little unrealistic. Just based on our society’s praise and promotion of capitalism, I felt like white collar crime would be something that would be easier to get away with. And especially with the financial crisis, there were a lot of people who did horrible things that weren’t persecuted and ended up paying people off.

So I guess that felt a little over-accentuated. Maybe if there hadn’t been as much external pressure on him, it could have been a little more relatable. I felt that Sebastian was going through an emotional crisis that in real life wouldn’t happen.

JK: Did you relate to Charlie and his story?

JC: I thought that Charlie was very sweet and he was a character I could relate to more, especially his awkwardness in trying to talk to people.

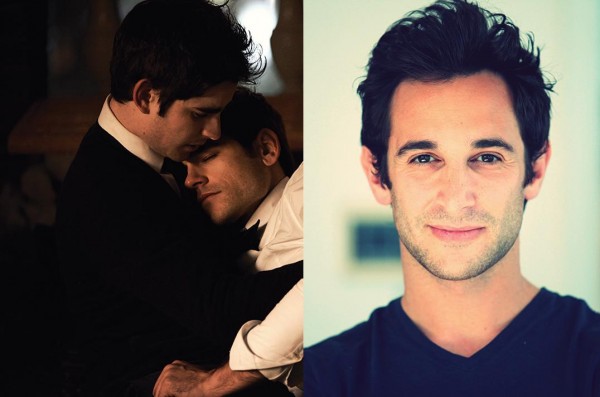

Charlie (Jonathan Gordon) cradles a distressed Sebastian (Jason Ralph) in “Those People” (c/o Little Big Horn Films)

JK: I set out to make Charlie the main character and the movie is his coming-of-age story. At the heart of it, that’s what it is. The way the coming-of-age genre typically works is that all the other characters have coming-of-age arcs as well, and that’s why Sebastian has his own. My goal was to have the audience relate to Charlie and go through this journey with him. And if not Charlie, find themselves somewhere in the movie, whichever character in the group it may be.

Whether you relate to Tim having been through something like this and you’re older and a little bit wiser, or the other friends in the group. But I didn’t make Sebastian the main character because I didn’t want to force the audience to relate to him. I would love if by the end of the film you understand him a bit more. And maybe you do relate to him, maybe you do feel something for him, but he starts out as a character who is unlikable. That’s the point of Sebastian. He’s basically the villain of the movie, if you think of what the definition of a villain is, which is an obstacle.

JC: Would you say that he’s the antagonist of the film?

JK: He is. Because he’s standing in the way of Charlie falling in love with another guy. So just by what the definition of what an antagonist or what an obstacle is, that’s what he is. But it’s not so cut and dry because I think the friendship at the center is the central thing.

JC: I suppose that came off as kind of confused to me while I was watching the film. I thought you were trying to get the audience to sympathize with Sebastian. There’s that line of dialogue that I think repeats a couple times, where he says something to the effect of “I’m not my father.”

JK: “You’re not your father, you’re everything.”

JC: Right. “Am I a good person?” “You’re the best person,” things like that. Because that was accentuated, I thought we were supposed to end up sympathizing with Sebastian. Which I agree that he’s an unlikable character. In the first scene, he’s distracting the main character from the cute piano player and he’s putting all the attention on himself.

JK: Right. Just to clarify, when I say he’s unlikable, I guess I should say that I made him traditionally unlikable. But I like him very much as a character. I think he’s fascinating and charming, and also awful, but I didn’t make it clear that he’s a bad person or a villain in the cartoon-y version of what a villain is. I love all the characters in the film. I’m not judging them. It’s not like I set out to make a satire on upper-class life. I think it’s best when you present these characters and each one thinks he or she is good in some way and let the audience decide for themselves. No one’s just good or bad.

JC: Oh, of course not. I wouldn’t call Sebastian just a villain either. I just didn’t find him very sympathetic or likable and I thought you were trying to make him sympathetic and likable. He’s the main character’s love interest, so I guess that didn’t quite add up to me. I didn’t quite see the film through that vision.

JK: Well I hope that by the end that the audience’s opinion of Sebastian changes. If he starts out unlikable, you end up gaining some sort of understanding for his character through his interactions with different people in the movie and what he goes through.

I should tell you that when I was screening the film to people during the editing process, I found that the audience was very divided between Sebastian and Tim. You would see that half of the audience loved Sebastian and was just in love with this character, Team Sebastian all the way. And the other half was all Team Tim. And it wasn’t like you could like both, it was very much like in Twilight with Team Edward and Team Jacob. People really plant their flag on one side or the other. So I’m not surprised to hear that you didn’t find him relatable or likable, because it’s definitely not the first time I’ve heard it.

Through the editing process, we really worked on that line of how unlikable to make him. On all our questionnaires during the editing process, one of the questions was always “Do you like Sebastian? If so, when did you start to like him in the film?” And we would watch as we edited the film and take out a line or a scene here or there that the answer would change very frequently. Through the shaping of the film, I think we put that line of his likability exactly where I want it.

JC: That’s interesting to hear that it was something that you took a lot of deliberate time to process and structure.

JK: Oh, yeah. I worked on the script for two and a half years and that was a big part of the writing process, getting people’s feedback and the opinions on Sebastian changing. We spent five months in the editing room working on that too. This has been thought about ad nauseam.

I once got a note from one of my producers, Sarah Bremner. When I was struggling with the audience not liking Sebastian, she was like “Joey, you’re never going to be able to please everyone. And if you try to do that, your movie will be bad. You just have to be okay with some people hating your movie.” There are some people who will never like a movie about this kind of character because they are so turned off by, for lack of a better term, “those people.” I kind of just had to make peace with that somewhere along the line of the writing process.

JC: Well, that’s very true. You definitely did not make a bad movie. I was very turned off by the narrative, by what I had interpreted as the depiction of wealth throughout the film. At the same time, I did think it was a finely made film and there were aspects of it that I thought were pleasing. This is why I struggled with the film so much. At the very least, I think you have a promising career ahead of you and it wouldn’t surprise me if this film did well. And if it did, I wouldn’t hate you for it.

JK: Well, from your mouth to God’s ears. Hopefully we’ll get distribution and a lot more people can see it.

JC: Yeah, I hope for the same. The main element that I think every critic and every person watching a film needs to keep in mind is that a lot of passion goes into filmmaking. Making a film, especially a feature, is a huge process. An opinion is an opinion. It’s a perspective. My perspective is influenced by my life, by the things I’ve gone through and the films that I have enjoyed.

JK: Just out of curiosity, what are some of your favorite films?

JC: That’s a good question. My top five that I typically recite to people is Rosemary’s Baby–

JK: Oh, I love that movie.

JC: Rosemary’s Baby? Oh yeah, it’s the best. It’s the best horror film ever made, in my opinion. Network, Requiem for a Dream, Harold and Maude and usually, for the fifth one, I’ll throw in Weekend, the Andrew Haigh film–

JK: Oh, I know that’s one of my favorite movies.

JC: It’s probably the best queer-themed film to come out in the past ten years.

JK: For sure. It’s so funny because both Rosemary’s Baby and Network I saw for the first time this year. For some reason, they’re two films that were just always on my list of movies to see and never saw. Rosemary’s Baby blew me away just because of the tone. You know, that tone is so strange and I feel like that movie would never be made today because it’s so upsetting at the end. It’s just so fucking bat shit crazy. But it was also so beautiful. I love that they always have someone playing “Für Elise” in the background from another apartment. I think it captured New York living in a really awesome way.

And then Network I just watched on the plane. Delta had it as one of their free movies and it was one I had always wanted to see. And it’s another one where my jaw was just on the floor. The writing is so smart and I love Faye Dunaway’s character.

JC: Oh, she’s perfect.

JK: I just love a fierce bitch in a movie. For my next movie, I really want to deal with a strong woman like that.

JC: For that role, she achieved perfection, in my opinion. She is just, from beginning to end, absolutely perfect.

JK: And it’s just mind boggling that Sidney Lumet made that and then Dog Day Afternoon within, what, like two years of each other? He was just on fire in his career at that point and Dog Day Afternoon is another one of my favorites. But I’m actually not a Harold and Maude fan, I’ll tell you.

JC: Oh, really? What about Harold and Maude did you not enjoy?

JK: I found it very twee. It was just a bit too cutesy for me, in some ways. So many people told me I would just love that movie and it didn’t really connect with me. But who knows? Maybe I was just in a bad mood when I watched it.

JC: Well, what really connects to me about that film is how previously in Hollywood you couldn’t depict gay people at all and it was all through code. Like with Hitchcock, you had people playing footsies and winking at each other as a way to say that they’re gay. The writer of Harold and Maude was actually gay himself. He died from complications due to AIDS in the late 80s, I believe. And there’s certain segments of that film where you can tell that his experience as a queer person directly influenced the content of the script. The intermingling of those two is just fascinating to me. How you can take a straight romance and make it kind of gay.

JK: Yeah, that definitely makes sense. But that’s definitely an informed reading of the film. You know, instead of just experiencing it and watching it. I wonder if I went back and watched it through that lens if maybe I’d appreciate it a little bit more.

Those People will have its final showing at the Seattle International Film Festival on Saturday, June 6 at 11 AM at the Harvard Exit Theatre (807 E Roy St).

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_-yM9ahuAeo]

Great dialogue! I look forward to seeing Joey’s future work.

Wow. Great interview. It’s wonderful seeing two people who (obviously) really love film interact with each other like that.

[…] Saturday, July 18th features a number of films (and a panel discussion) related to Transgender Cinema including the Susan Sarandon produced film, Deep Run. Narrative fiction films for Saturday include the German film, You & I and Those People, the New York drama from director Joey Kuhn that we extensively covered during SIFF (articles HERE and HERE!) […]