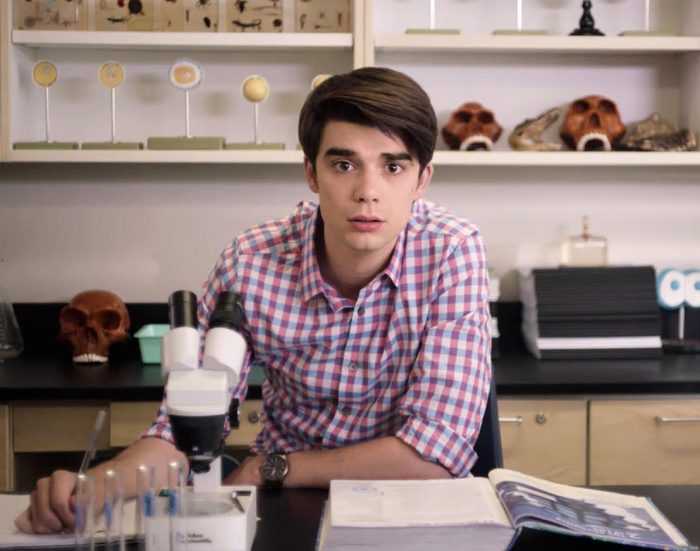

The cast of indie LGBTQ film, BEACH RATS opening in Seattle on September 8, 2017 at SIFF Cinema at the Egyptian

Beach Rats is a new film from writer/director Eliza Hittman that delivers a steady-handed, even-keeled and deliberate depiction of Frankie, a drug-taking, sexually-conflicted young man growing up “aimless” and “delinquent” in “bleak” Brooklyn NY USA.

I use quotations on certain words above because they are from the film’s description on its own website, and they are quite accurate. Prepare to see plenty of beautifully-shot aimless delinquency in bleak NYC. Prepare also to not feel too strongly about it. You will neither laugh nor cry. You will witness. You will observe. You will think. And you will leave glad for the experience, perhaps wondering exactly why.

What Beach Rats is not is a mindless beefcake gay film. Bodies are on display, especially on its poster; and soft-core sex of both hetero and homo varieties is portrayed; but while there could be some titillation here for some viewers, the sex is… troubled. It happens always in slightly disquieting contexts tinged with anxiety, awkwardness, desperation or even danger. I found myself wondering what was about to go wrong during each sex scene. What terrible thing is about to happen? But as with everything in Beach Rats, this was a low-grade sensation; more generalized worry than full-blown fear. That’s how emotion works in this picture. It’s a flat field, as Peter Murphy once sang. The difference here from the Bauhaus lyric is that I never got bored in Frankie’s flat field, mainly because of that lingering background radiation of light anxiety and tension.

Beach Rats is the somewhat-but-not-too-powerfully portrayed story of a young man who struggles, slightly, against a mostly toxic milieu but who ultimately fails to change it or himself. Frankie and his little rat pack of scummy friends aren’t going to Hollywood. They’re stuck in their shitty, dead-end lives. As such, it’s more cautionary tale than feel-good movie; an oddly nostalgic throwback to a darker, shame-ridden gay cinema of the not-so-distant, pre-Obama past that reminds us that we’re not in Oz anymore. Not everyone lives in a technicolor world of normalized same-sex attraction. And if that is home, I don’t want to go back, Scarecrow. Auntie Em and her greyscale farm can fuck off.

But I digress. Back to the subject of tone.

Beach Rats performs on its viewers a kind of emotional edging. You might find yourself always on the verge of an emotion. You might find yourself sensing a change, or a reveal, or a deepening of conflict that might eventually resolve. Nope. There is no pat film-school structuralism here. Beach Rats plays against dramatic expectation. It does not pay off. There is no climax, just as one suspects there will never be any pay-off or climax for Frankie himself. This is no Good Will Hunting. There is no deeply insightful Robin Williams to rescue the secret genius of Matt Damon. This Will Hunting is only marginally intelligent and rather bad. There is no catharsis of one man weeping into another man’s sweater here. This is massage sans full release. No release for you. Remember our hashtags: Aimless, delinquent and bleak. But not too much of any of it. Beach Rats is neither feel-good nor feel-bad. It is feel. But feel what exactly? And how much, if at all? This is its core pleasure.

A scene from indie LGBTQ film, BEACH RATS opening in Seattle on September 8, 2017 at SIFF Cinema at the Egyptian

Speaking of pleasure: Frankie doesn’t know what he’s into. He doesn’t know what he likes. He bristles when people try to pin him down. He’s clearly an expression of the classic changeling archetype, except that he never changes. We know what he’s into, though. We know what he likes. We’re no idiots, sitting in our theater seats. We see him do what he’s into and what he likes. And that makes us think he’s the idiot. You’re the idiot, Frankie. You. But if we’re honest, we also see that he’s a reflection of ourselves, because we walk around confused about ourselves, to varying degrees, even though we, like Frankie, often do exactly what we want, even when we think we are stuck in some hell of unfulfilled desires. We cling even to our pain. That, too, defines who we are. And this is at the heart of what makes Beach Rats watchable. Frankie evokes empathy. Frankie is the world. Frankie is life. And he is frustrating, dislikable, disagreeable, aimless, delinquent and bleak. Everything we love and love to hate, all wrapped up in one druggy, twenty-something teen.

I’m old enough to remember the dark days before the internet turned cruising into an easy-breezy, swipe-and-tap app experience. From that perspective, Frankie’s internal conflicts seem anachronistic and slightly annoying. What’s his problem? He encounters plenty of guys chilling online waiting to bang. His present is the sexual future we were promised in Logan’s Run. You kids today have it too easy, et cetera. But of course we all have problems that run contrary to the actual possibilities of life, don’t we? We’re all kind of nose blind to our own reek, as it were. Or we like it. Or others do, as Frankie’s not-quite-girlfriend says to him in bed: “You stink, but I like it.” But does this make Frankie an apt symbol of today’s youth growing up in a world where gayness is supported by federal law but also still reviled? It’s a thesis that Beach Rats seems to explore in its own oblique way – or perhaps more accurately, prompts us to explore in reaction to it.

As I said, Frankie neither learns nor grows. While he doesn’t change over the course of the story — usually a cardinal sin in conventional storytelling — our perception of him does. Sometimes we sort of identify with him, other times we somewhat dislike him. This tempered dynamism happens in the viewer in response to a complete lack of dynamism on screen. It’s a strange experience, and one that should be had if you are at all a fan of emotionally complex, evenly-paced cinema. Prepare to encounter existential questions, and to arrive at no easy answers.

So go forth and brood, my friends, for the virtual internet-cruising is real, and there are many pleasures to not-quite-be had. As Frankie says to a potential trick: “Are you going to make me say it? Let me see your dick.” Date movie? Maybe. Sure. Grindr someone and take them to Beach Rats. Blur the line between fact and fiction. Maybe go easy on the prescription drug abuse, though.

Beach Rats debuts on 8 September in Seattle at the SIFF Cinema Egyptian. It might be the “realest” movie about bisexual, drug-hounding white trash that you’ll see all year.