Local theater companies seem to prefer staging very recent work or revisiting plays from the 1980s or 1990s rather than going further back in theater history or exploring European theater…much to many theater lover’s regret. Staging recent work is important, but so is experiencing interesting plays from the more distant past as well as dramatic literature that challenges.

And, when theater companies do explore older works, they tend to head straight to a handful of writers: Shakespeare, Ibsen and Chekhov. Maybe because most of that original work is old enough to be in public domain but it’s also easily accessible. Familiar. Part of the canon. Reassuring costume dramas.

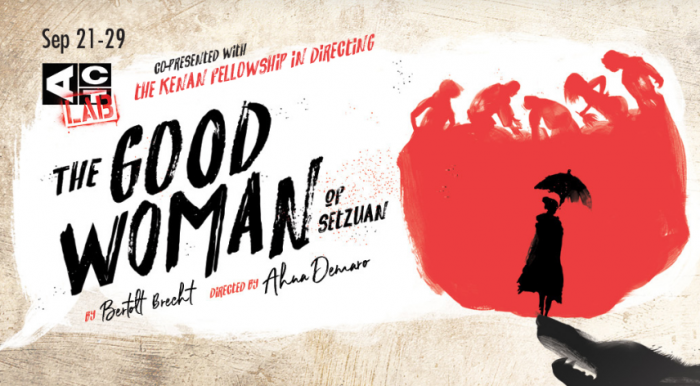

Meanwhile, one of the great masters of mid 20th century theater tends to get ignored of late. The prickly, if not prick-ish, German playwright Bertolt Brecht created major works like The Threepenny Opera (with Kurt Weill’s music), Mother Courage And Her Children, The Caucasian Chalk Circle and The Good Woman of Setzuan (sometimes known as “The Good Person of Setzuan”) and many others but Brecht’s complicated politics as well as the complexity and style of his work make him a tough choice for theater companies. Brecht isn’t “easy”.

But, Brecht was a challenge that director Ahna Demaro wanted to tackle as part of her work at ACT this year, as their Kenan Directing Fellow, a much sought after fellowship position in theater that allows theater makers pursuing upper graduate degrees a change to work in major theater companies in the United States. At ACT, as part of the fellowship, each fellow directs their own theater production, within the confines of ACT’s studio space, The Eulalie Scandiuzzi Space. Ms Demaro is a recent graduate of the University of North Carolina School of the Arts and the first female fellow in ACT’s program.

Ms Demaro chose The Good Woman of Setzuan to stage, in a production that opens (tonight) Friday, September 21 and runs through September 29. (Tickets are only $10; available HERE). Since ACT did such a terrific job of summarizing the basic plot of the play:

A world built on greed rather than empathy will always turn its back on the good in a person.

Three gods in search of lodgings are taken in by Shen Te, a poor girl who sells herself to make ends meet. In exchange, the gods give her favor, fortune, and the title of “a good person”. Shen Te desperately tries to live up to her new status, but her neighbors see only opportunity in her kindness, forcing Shen Te to create a male alter ego, Shui Ta, to protect herself from being torn in two by the selfish nature of her world. Brecht’s classic parable seeks to expose the contradictions within our society, and asks the question: Is this the world we want to leave our children?

We managed to snag Ahna Demaro during this busy final production week for her and this production to answer a few questions about “The Good Woman” and why it’s an important show for today’s audiences.

Ahna Demaro, center, directs actors in her production of Brecht’s “The Good Woman of Setzuan” at ACT

SGS: The obvious first question: Why did you choose this particular play? Brecht isn’t much produced anymore (sadly). It’s not easy for a director/production to capture that “Brechtian” tone. Why this play and this challenge? Are you a Brecht fan?

Ahna Demaro: This play for me is so pertinent for our time. It talks about what it means to be good in a world ruled by money. It talks about a world filled with smog and gunfire, and although Brecht wrote this post-WWII, not much has changed today. The air quality, even here in Seattle recently, is worse than ever, and we continue to fight a seventeen year war overseas.

(And) I do love Brecht. His play Caucasian Chalk Circle, usually publish side by side with “Good Woman”, is another compelling story based on the age old parable of two woman who both seek custody over the same child, and the emperor tells them both to tug on the child, and whoever tugs hardest wins. This story also deals with the struggle between classes, with the idea that money is not always the answer, but that care and showing up count for more. Brecht was always very conscience of the world he lived in, and I think that’s why he’s still relevant even today. His stories have a strong voice about the struggles people were dealing with, and the trick to his language is figuring out why people are saying what they say, and what it truly costs them.

That being said this was truly a monster of a play, much larger than I had ever anticipated. Taking over 25 characters and fitting them into 5 actors was quite a challenge, but one I was happy to take on. This play quite possibly may be the hardest thing I’ve ever done. I’d do it again in a heartbeat.

SGS: In our current time with gender as a “hot topic” with the rise of the transgender community’s equal rights movement and the concept of being “non-binary” or breaking the male/female binary, this play seems especially timely. Did the current discussions and gender identity movement influence you at all in choosing the play and how you cast it as well as its direction?

Ahna Demaro: I felt strongly about holding true to the translated title of Good Woman, instead of Person, only because of something Eric Bentley said in his introduction, he said, “This human being is a woman. Is that a weak word, a soft word, as one critic of my title has said? Depends if you think all women are weak and soft.’ Brecht taps into a very recent shift in our history. Not even a century has passed since a gender that makes up half the population was given an equal voice in the building of our very own nation. And in an even shorter amount of time, we’ve managed to push the boundary of gender as a concept so that it lives in a fluid realm. One that we continue to explore as we deconstruct the binaries of our history.

Women’s suffrage had existed no more than thirty years when Brecht wrote “Good Woman”. For the first time in history, women were taking on men’s jobs in factories, working on naval yards, welding, evening diving because the war had taken so many men that there was no one to continuing supporting the war. Brecht taps into this shift as he creates a girl with no agency save the sale of her own body and transforms her into a ruthless, cunning businessman that finds ease and wealth through doors that could never open for the very same girl.

We cross-gendered in casting because it was necessary, but also because it’s irrelevant, and I don’t mean that unkindly. The things these characters need are not unique to their gender, perhaps to their class. Sometimes Shen Te and Shui Ta melt together because much like the lines of binary gender, both of these selves live in the same body. Shen Te tries to separate pieces of herself she does not wish to be into a bad business man, but everything she does are choices she makes with the same soul. We are all hard and soft at times, bad or good, people are not made to fit in binaries, everything about us is fluid.

SGS: The Good Woman of Setzuan isn’t exactly a small show…lots of characters, lots of plot, an “exotic” setting. How do you fit all that into the confines of the Scandiuzi, an intimate black box theater? Is that a challenge or does it help enhance the work?

Ahna Demaro: I had an amazing team of designers. We all worked together to really build the world. Kat Laveaux’s costumes do a wonderful job of transporting you to a world that lives perhaps somewhere in the future, while also giving the whole thing a certain fairytale quality. We thought this was important because we didn’t want to be stuck in the bounds of an accurate historical world, we wanted to have the freedom to play. Amber Parker talent with lights does an incredible job of shifting us back and forth from the world of the Gods to the land of the people. Andre Nelson’s music is simply lovely. Alexander Winterle helped to create the floor and the world, and find the pieces of history that will inevitably end up beneath our feet, stomped into the ground without a thought.

SGS: If “Setzuan” hadn’t worked out for your Fellowship production, did you have a back up production?

Ahna Demaro: I think “Chalk Circle” was an idea, but it has even more characters than “Good Woman” and they’re all on stage at once, so it would have been ridiculous. I read Lobby Hero (by Kenneth Lonergan; seen on Broadway this past season) a few times, but it didn’t quite hold the story I wanted to tell. I fought for “Good Woman” because in a world that has such a huge divide between the rich and the poor, the 99 and the 1 percent, it’s a story we need to keep telling. We have to restructure our world. Depression and anxiety are linked inextricably to not simply poverty, but the divide between the impoverished and the wealthy. In countries where everyone’s poor, these issues do not exist. I once had a teacher tell me in college that to compare was to despair. That if I was always holding my work up to others instead of looking at my own progress, I would always be unhappy, and yet it’s impossible not to. The gulf between the classes, the ineffectiveness of supply-side economics aka ‘trickle-down economics’ — it’s all a problem we have failed to work out. There must be a better way.

Ahna Demaro is a recent graduate of the University of North Carolina School of the Arts with training in filmmaking, acting, and directing. She is the second of two Kenan fellows for ACT’s 2018 season and the first-ever female fellow. The Kenan Fellowship in Directing at ACT is made possible in partnership with and support from the Thomas S. Kenan Institute for the Arts as part of the Career Pathways Initiative. Recent graduates of the UNCSA undergraduate and graduate programs from the School of Drama are eligible for the Fellowship. ACT is one of only a few prestigious theatres in the United States to host a Kenan Fellowship.

The Good Woman of Setzuan runs September 21-29, 2018 in the Eulalie Scandiuzzi Space at ACT Theatre, 700 Union Street in downtown Seattle. Tickets are $10 and may be purchased at acttheatre.org, by phone at 206.292.7676, or at the ACT Ticket Office at 700 Union Street.