Alice Gosti’s new piece of dance theater with her 10 artist company, is “Material Deviance in Contemporary American Culture” playing through Sunday, April 1, 2018 at On the Boards.

Too.

Much.

Shit.

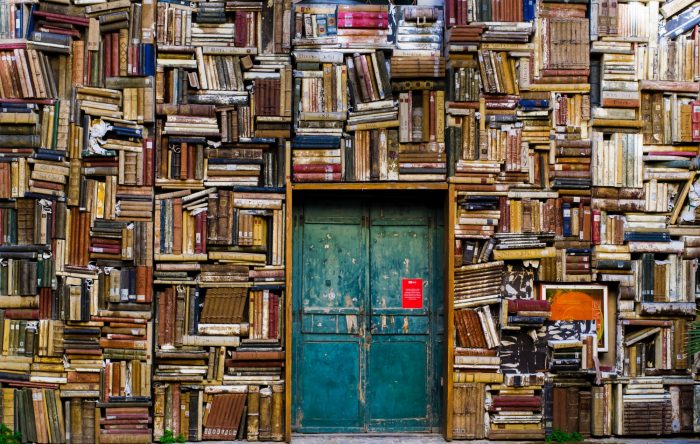

That’s about the only impression that came to mind when the stage was revealed: huge shelves on rolling palettes, all completely covered with household “stuff” — boxes, bags, bears, a cat litter box. Stuff, endless stuff, all neatly set up on its towering movable taxis.

The size of the stuff dwarfs the dancers as they appear one by one on stage, and are not only dwarfed but physically divided by it. Through its sheer enormity, the stuff takes center stage, both literally and metaphorically.

And that is very much the premise of Alice Gosti’s new work, with its fittingly unwieldy (but descriptive) title, Material Deviance in Contemporary American Culture, playing through Sunday at On the Boards. In this modern dance/performance piece, ensemble members interact with each other and the piles of stuff, but their movements are constrained by their surroundings. Where On the Boards’ main stage is normally roomy enough for plenty of performers, here all the stuff leaves the ensemble of ten little space to work with.

Over the course of the show, the enormous taxis are moved judiciously, infrequently, and always very slowly. They are huge. Their ultimate resting place in each scene sets the whole stage, determines the area in which the dancers may move, how close they must play to the audience, and how divided and compacted they will be.

I have never found myself so closely tracking the set’s movements as I did in with this piece, but their arrangements here demanded it. During the show, I sketched the positions of the taxis of “stuff” on a program; after the show, I found myself mapping it out, tracing the telling of the story and the feelings accompanying it based on the positions of mountains of stuff. In those different positions, the stuff towered, it divided, it constrained; and if nothing else, even when largely out of the way, it distracted. It overwhelmed.

The metaphor was not hidden. As modern dance goes, this piece was about as accessible as it gets, placing little demand on the audience to mine for its meaning and follow along. And yet, for the many of us affected by hoarding and its ilk in meaningful ways, it was a very touching and emotional piece. It was also, frequently, liberating — to know that others experienced closely a phenomenon that was always held as shameful, that no one else wanted to talk about, that explained why one never could find their homework as a student, or could never have classmates over, or could not seem to keep their stuff together.

Oh yes, that was me growing up.

You too?

In one scene there are text messages, then calls, with catalogs of the stuff an adult child must accept from her mom in order to keep the stuff “in the family,” or because “I thought you liked that one,” or in anticipation of “well you’ll have a big enough place eventually.” It’s the hoarding parent that can’t help but share the wealth of valueless things — and the guilt, and the attachment. If you don’t take the stuff — how heartless are you, anyway?

Oh yes, that’s my mom.

Yours too?

Likely acknowledging the frequency of these attachments, Gosti’s project opened the doors for a “community ritual” last Sunday, before opening this week. She invited people to bring things to which they had attachment but were ready to part with, and give them to the piece. This is where at least part of the endless piles originated — and perhaps the door prizes too. (Each program came bagged with a small trinket of some sort, thus providing every member of the audience a new thing to get attached to.)

The ritual was functional for the show’s acquisition, but also functional for community members seeking ways to let go. By giving donors’ no-longer-needed stuff a new purpose, and by allowing givers to tell the stuff’s story as part of the parting (perhaps recognizing what Thane Rosenbaum, in The Myth of Moral Justice, described as the relief that comes from telling the story), the community ritual facilitated an acceptable space for the donor to let go.

Throughout the work, Gosti illustrates these attachments and interactions with stuff through several creative scenes, various in types of movement and staging so they never drag on (with one exception, presumably purposeful, which I’ll get to). In one, a teddy bear is projected in shadows on a wall, looking creepy in its hugeness; it moves and poses in the shadows, humanlike; and finally it emerges from the shadows in human form, perhaps showing the frequency with which people give human-like significance in particular to childhood stuffed animals. Another, the dancers sit around a table, playing close to the audience due to the arrangement of stuff behind them, furiously clipping ads with scissors like some epic coupon battle. Another, fresh from trying to put things away, the dancers stream across stage, shopping, endlessly, passing by over and over and over again — WILL IT EVER END?? Of course, in real life, it will not.

As far as messaging goes, that endless shopping sequence — in which nary a word is uttered, though the action is unmistakable — is about as loud as the performance got. Overall, the piece felt quiet, while allowing the stuff to be very loud. The movements were likewise “quiet” ones — this was not a show of high kicks, leaps, or bounding across stages. Instead, the movements were small, and much of the difficulty was in their smallness, their jerkiness, their frozen positioning requiring great strength. About the “loudest” of actions arrived during the “coupon battle” scene (as I have termed it), as electronic music pulsed and ensemble member Alyza DelPan-Monley pounced up on the table and posed in different stances with jaw-dropping control.

In an interview with Crosscut before the show opened, Gosti revealed that she does not offer up opinions in her shows, does not tell people what to think. She asks questions, investigates an issue, then leaves the audience to think and grapple. This piece did that exceptionally well. Hoarding, over-consumption, shopping therapy, materialism — they are all pieces of the same phenomenon, a connection with or desire for physical things that overtakes emotions and relationships and, in many ways, defines sense of self.

The show does not judge. It does leave with a demand that we evaluate our relationship to things, and to the very-American premise that freedom means nothing if not the ability to buy and consume whatever the hell we want. (And, though the show did not go there, one timely application is to suggest that the freedom to buy is a fierce motivator of many Americans’ insistence on the continued availability of assault rifles — another example of stuff-freedom overriding relationships, community ties, public health, and logic.)

The Artistic Director of Sound Theatre Company, Teresa Thuman, has a habit of saying of theatre artists, “We are sculptors in ice” — creators in a transitory medium, and when the show’s gone, it’s gone. How true it is, and for Gosti’s show of only four days it’s especially true. What a shame that is. For all I hate (hate, hate, hate!) the descriptor of “universal” when applied to virtually any experience portrayed onstage, here the descriptor at last rings true. Not the hoarding, which is hardly universal (though it is sneakily common and probably hugely under-acknowledged or reported), but the overall relationship with stuff. Our relentless pursuit of material goods, emotional relationships to that “stuff,” and the barriers it erects between our abilities to relate personally with other humans — that is the modern American story, if anything is.

It’s a shame that the performance just witnessed is ice — halfway melted now, gone too soon. This is one of the rare shows so many of us need to experience — to self-examine, to re-evaluate our relationship to stuff, and to challenge our behaviors as a country that permit acquisition to constitute freedom, even as it’s boxing us in, and out.

Alice Gosti’s piece plays through Sunday (4/1) at On the Boards. Find out more about Gosti’s work here: http://www.gostia.com/.

While you’re at it, look up the rest of On the Boards’ 2017-18 season: https://www.ontheboards.org/1718-season. This season’s pieces are widely varied and unique; and since they only run four shows at most, you probably won’t have time to wait for a review and think about it.