Seattle Repertory Theatre’s Strong Production of Dietz’s Compelling 2004 Play Opened January 23 & Runs Through February 10.

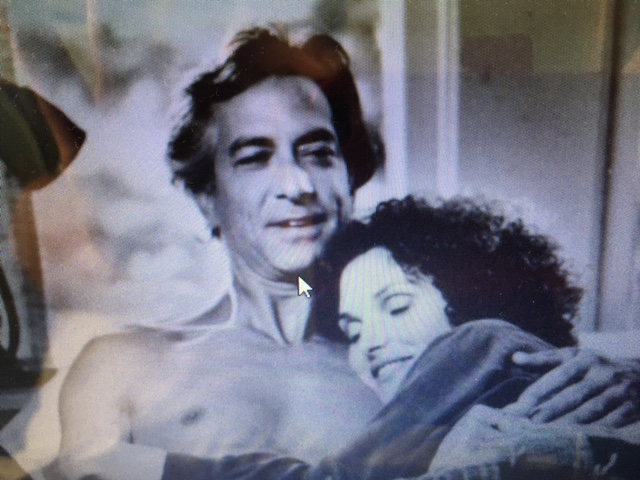

Kevin Anderson in Seattle Repertory Theatre’s production of Last of the Boys. Photo by Alan Alabastro

Steven Dietz has a way of taking the absurd things you might overhear while watching strangers in public, and finessing them into believable, extraordinarily human plays. His plays transport — making the characters and their dilemmas on stage real, and affecting.

A good example of that is Dietz’s 1993 play Lonely Planet, revived around the nation and locally produced at West of Lenin last year. (See my interview with Dietz on that production here.) In that two-hander, one character keeps bringing in chairs — piles and piles of chairs — from the street into a cozy map store. The shopkeeper hollers at him to take the things out of there; but he won’t, because they’re from his friends who have died of AIDS, and the shopkeeper won’t, because the crisis has left him afraid to leave the store at all. All this comes out as the two, who are old friends, just talk with each other in the store, which no one else ever comes into. As the chairs pile up, there’s a looming sense that the shopkeeper can’t hide there forever, while the magnitude of the crisis keeps growing, and growing, and growing, in plain view.

Onward to Last of the Boys, which opened this week at the Rep and centers on a similarly awkward-but-deep friendship among two men. The two old friends, both veterans of the Vietnam War, volley insults, stories, and exasperation back and forth; one of them has escaped virtually everyone by camping out in a trailer on a Superfund site, while the other follows his favorite band around with a sign he won’t stop toting until all the band members see and heed it. Both men avoid stories of the war that bound them together 35 years back (the play was first produced in 2004 and is set in the early 2000s), until the wall keeping the topic off-limits begins to crumble around them. Or rather, their solitude and camaraderie is invaded, first by a funeral and visions of a soldier’s ghost, then by two women who are dealing with ghosts of their own from the war.

Direction by Braden Abraham is strong, keeping the characters’ quirky and disagreeable personalities forefront, while maintaining some empathy for them; at least for me, the play never causes its characters to teeter over into unlikable and irredeemable. Abraham’s direction deftly maintains the seclusion of the setting (both geographically and other-worldliness) even as all sorts of personalities and activity intrude upon it. All that said, sit close: for while the stage is huge and in that sense is suited to the Bagley Wright theatre (the Rep’s largest stage), I’m not sure it’s a play that works well from too many rows back.

Crucially for this character-driven play, the casting is great: Reginald Andre Jackson and Kevin Anderson as the two leads (Ben and Jeeter, respectively); Emily Chisholm and Kate Wisniewski as the two women (Salyer and Lorraine); and Josh Kenji as the soldier.

Two local standouts are Jackson and Wisniewski. This past season, Jackson won the Gregory Award for Supporting Actor in Two Trains Running, also at the Rep; and he has a very recent history with Dietz, starring in last year’s production of Lonely Planet at West of Lenin, which Dietz also directed. In those productions, plus a strong performance in Intiman’s Stick Fly and numerous other roles, Jackson has established himself among Seattle’s most engrossing actors. And it was a treat to watch Wisniewski in this role, as a hard-drinking, road-hardened single mom outside a trailer — a far different environment from the recent Shakespeare performances (with upstart crow collective and Seattle Shakespeare Company) I’ve seen her in recently.

Another star? The set, by G.W. (Skip) Mercier, which is excellent. Shadowy hills loom behind a trailer with a dirt yard, fire pit and dumpster, where one vet lives alone to escape everything else. The lighting design (by Ben Zamora) makes the sunrise come alive and the low-burning fire pit seem real; while the sound design (from Victoria Deiorio) is perfectly unobtrusive except, that is, when the sounds of attacking warplanes are bearing down overhead.

The play hops in and out of the war zone, which left some audience members audibly confused after the show. I understood it as all physically set in modern times, with ghosts of the past being established very much in the characters’ present. But you can take it however the spirits move you.

This play is one that could be hopelessly dark, better left alone like we seem to prefer to do with Vietnam and its veterans alike. But it demands better. It’s an acknowledgement of the dark, tragic, terrible aspects of the era — one description of wartime atrocities in particular was horrific — but an acknowledgement too of the people the United States forced overseas, their humanity and character and humor, along with the people left behind but still deeply affected by the war.

Last of the Boys, like Lonely Planet, is a play that’s funny and tragic and refuses to forget. It’s highly recommended.

Last of the Boys runs through 2/10 at Seattle Repertory Theatre; see schedule and tickets here. Tickets up to $82. (Financial accessibility note: the Rep offers discounted tickets for same-day rush, as well as complimentary rush tickets for theatre industry and TPS members; bus service to Seattle Center and Lower Queen Anne is ample; free street parking in the area is available on Sundays but can be hard to find; paid garage and metered street parking available other days. Gendered bathroom policy: the Rep encourages patrons to use bathroom matching their identity, which is posted at restroom entrances though policy doesn’t well accommodate non-binary-identified people. There is one single-stall, gender-neutral bathroom near the Bagley Wright theatre entrance, accessible by talking with house manager. Physical movement accessibility: the Rep is wheelchair accessible. See additional accessibility info here.)