The Tacoma-area theatre’s production, told in six acts across two separate shows — is worth the commitment. It runs through March 17th

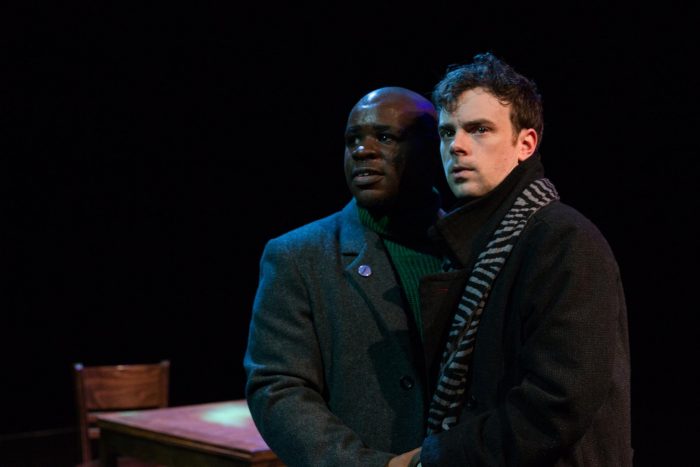

Belize (left) (played by Ton Williams) and Prior (Kenyon Meleney) in Angels in America: Part II (Perestroika). Photo by Tim Johnston.

Staging Tony Kushner’s two-part epic, Angels in America, is no easy feat. There’s some theatre magic in making the angel’s earthly visit a powerful one; strong acting required to bring loathsome characters to life in a way that’s compassionate and complex, too; and an audience willing to come along on the journey into a particularly dark era of recent American history, who’s also not afraid of gay sex and religious themes and Republican politics. (And yes, you’ll get all of them in this production.)

And then there’s the most obvious reason the show is so hard to stage: the whole thing, with intermissions (four of them in total), runs almost eight hours long. It’s a beast for the actors and crew, clearly; but it’s no easy feat for an audience to commit to, either.

The surprise with Lakewood Playhouse’s production of the saga isn’t necessarily that the theatre took on the challenge of staging both (in repertory), but how well they did with it. And it’s particularly stunning that they performed so well when both shows are held in one day, as was true of the Sunday marathon I attended.

Part I (which the Playhouse stages on Wednesday, Friday, and Saturday nights, and Sunday afternoons) is titled Millennium Approaches, and introduces the world of the intensifying AIDS crisis. In this world, there are two key types of fear: for “out” gay men, the fear of contracting the virus is paramount; and as lead character Prior begins getting sick, his long-term boyfriend Louis leaves him rather than care for him and risk more exposure. (The perceived risk can’t be the entire reason, though; in a moment of self-loathing, Louis has sex in a park and tells the stranger, “Infect me. I don’t care. I don’t care.”) And then there’s the pervasive theme of closet culture and the second type of fear: that which consumes men in power, and in this case powerful religious and politically conservative Republicans, of being outed. Although it’s largely to set that world, the inter-character conflicts and relationships are exceptional; and this production gives an excellent treatment of them, making each character compelling and with tight direction that moves the piece along quickly. It doesn’t feel like a three-plus hour show; and while the characters may disappoint in some of their life choices, the actors playing them never disappoint in creating them onstage.

Louis (left) (played by Jason Quisenberry) struggles with whether to leave his long-term boyfriend, Prior (Kenyon Meleney), after learning Prior is sick. From Angels in America: Part I (Millennium Approaches). Photo by Tim Johnston.

The second Part (held on Thursday and Sunday nights) begins where Part I left off, in the heat of the crisis and with two main characters obviously in various stages of near-death. Called Perestroika, Part II considers whether there can be hope for rebuilding, its purpose made clear from the top of its first scene:

The Great Question before us is: Are we doomed?

The Great Question before us is: Will the past release us?

The Great Question before us is: Can we change? In time?

It’s an important but underappreciated aspect that this production requires a deft hand (from director and actors alike) that balances the humor and wit throughout the play with the dire circumstances at its center. In this production, Lakewood has put together a strong cast who excelled at the challenge.

The cast and director John Munn (who’s also the managing artistic director of Lakewood Playhouse, along with directing the current run of A Little Night Music at Tacoma Little Theatre) spent an extraordinary amount of time together working toward the show. The total rehearsal process ran a whopping eight months — designed both to give the actors time with the 250 or so pages of material, but also to allow them breaks from it. Per Munn, the ability to spend time away was key, allowing the actors to work on other shows early in the process, as well as to save themselves emotionally from being absorbed full-time in the material — which is, after all, an epic about deep homophobia, death, and the AIDS crisis.

Munn observed that the lengthy process gave the cast the time not only to acquire an intimate knowledge of the play, but to become bonded together as family; and he praised the dedication of the actors and stage manager, Melissa Avril Harris. Munn noted that as volunteer actors, most of whom hadn’t worked with him before, their commitment came strictly due to the richness of the material, and their passion for the show, the characters, the story. (Some of them also had deep personal connections to the material; see interviews with Munn and a few of the actors in the Tacoma News Tribune, here.)

From the audience view, even without any of the backstory, the dedication and preparation shows — not only because none of the actors noticeably flubbed lines or cues (which sounds basic, but we’re talking seven hours of material here … ), but because they were all clearly committed to their roles. There were several standouts. But let me be clear: all of the actors, individually and taken as a whole, did exceptionally well with this show.

Among the standouts: Kenyon Meleney as Prior and Ton L. Williams as Belize (and other roles), both of whom gave all the sass and fear and compassion and feelings their roles desired; and W. Scott Pinkston as Roy Cohn, the wretched, closeted, powerful and power-hungry, compassion-less asshole, who also happens to be facing mortality from the plague he’ll order doctors to deny he has, while his Republican counterparts in the 1980s enjoy their willful blindness and stymie any progress in fighting the disease. (Cohn was a real person, famous for his role in the McCarthy hearings as a ruthless and unscrupulous lawyer, and mentor to and power-buddies with the disaster sitting in the White House; read more on him here.) (Editor’s note: Roy Cohn was also an adviser to a young Donald Trump in the 1980s).

Ethel Rosenberg (left) (played by Jennifer Niehaus-Rivers) taunts a dying Roy Cohn (W. Scott Pinkston) in the Lakewood Playhouse production of Angels in America: Part II (Perestroika). Photo by Tim Johnston.

Jennifer Niehaus-Rivers played Ethel Rosenberg, and did so with a self-satisfied snark and justified vengeance, seared into memory long after the show. She also played Hannah Pitt, the rather naive mother of Joe Pitt (another closeted conservative administration Republican, and Roy Cohn’s prized rising star), who has just moved from Utah to New York and volunteers at the Mormon visitors’ center. Hannah is an endearing character because she seems so straightforward — small-town, religious, homophobic — but above all is deeply compassionate. She is, it turns out, about the only one who will care for Prior in his times of greatest need.

Playing Hannah’s son, Joe, was Joe Regelbrugge, who played it perfectly buttoned up — in both appearance and personality — as the golden-boy, closeted gay married Mormon Republican. The character’s values and ethics provided a nice contrast to the play’s other power jockeys, while maintaining an obvious hypocrisy in his personal closeted life (along with his strained heterosexual marriage and anti-gay politics); it’s a palpable relief when he finally begins to come out.

An actor I’m warming to — and hope to continue seeing develop with difficult material — is Jason Quisenberry. As Louis, Quisenberry was at his strongest in quiet conversation with any of the other characters, and had particularly strong rapport with Joe, his furtive lover. Things went a little off in heated conversations with Prior, when Quisenberry’s tone went up an octave and stayed there, which got monotonous fast and deviated from the otherwise convincing real-life exchanges. (Incidentally, this was my issue with the same actor’s performance in Martin Sherman’s Bent, with the Changing Scene Theatre Northwest, last year; though this performance shows tremendous growth in that short period.)

Erik Hill showed incredible range, playing a lot of roles — from a rabbi to a conservative crony — and playing them well. Shannon Burch ably played Harper Pitt, finding her own as her neglectful closeted husband eventually found himself. And Rachel Wilkie played the angel, sounding the voice of prophecy before memorably bursting onto the scene.

Staging was simple, with essentially a couple of beds, a hospital bed, and a table, though the angel’s entrance required some extra work. Sound was basic, with the flying sound of the angel’s wings as a standout. Lighting wasn’t anything special with effects, but did help designate the scene changes and move them along well. The enormous range of costumes, designed by Stu Johnson, were right-on.

The main problem with the show came in the pacing of Part II, the longer of the two (which weighed in at a full four hours the night I saw it). Not to knock the epic, but Part II, in my opinion, has a fair bit of fat that could be trimmed. As a welcome gift to the audience, a way to combat that in a production is to speed things up in some areas, to keep it moving along. Instead, some of the dullest of sequences were dragged out, resulting in significant chunks feeling glacial in pace. In contrast, all three acts of the also-hefty Part I (around 3.5 hours) flew right by.

From a writing perspective, Part I also contains the meatiest dialog, the most significant character development, and the most realistic of exchanges. And although some theatres choose to stage Part II as a standalone (inexplicably, in my view), it really doesn’t have the same power when separated out from Part I, vs. Part I operating well in its completeness as a stand-alone. For those reasons, although it’s best to aim for both, if you’re choosing between them, Part I is the must-see. Numb ass be damned, Lakewood’s Angels: Part I is one I could happily sit through again.

Angels in America runs through 3/17 at the Lakewood Playhouse, just south of Tacoma (Part I: 7 pm Wednesday, Friday, Saturday; 2pm Sunday) (Part II: 7 pm Thursday & Sunday). Tickets $26 (each part), available here. (Financial accessibility note: all Wednesday & Thursday shows are pay-what-you-can, and are not available online; ample free parking on-site; Lakewood Transit Center is next door. Gender-neutral bathroom policy: first-floor restroom is gender-neutral, single-stall. Physical accessibility: Lakewood Playhouse’s main level is wheelchair accessible; attendees with long legs or other mobility needs should aim to reserve front-row seats or those on the sides, as rows are extremely narrow.)

Lakewood Playhouse has partnered with Pierce County AIDS Foundation (PCAF) to distribute information at the show; info on PCAF here.