Cake, candles and a wish for more HIV cures

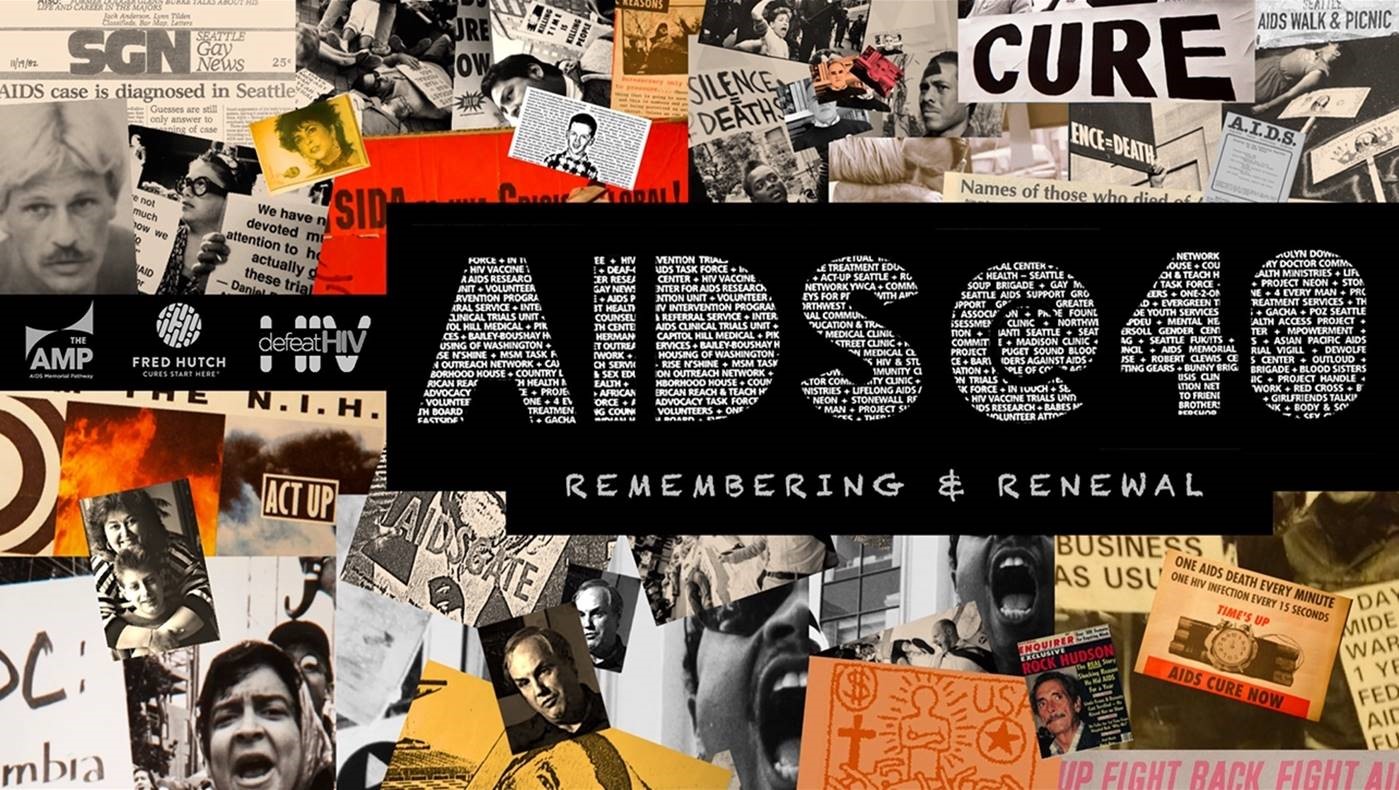

An HIV workshop pays tribute to Timothy Ray Brown, whose cure 10 years ago fueled research — and hope

By Mary Engel / Fred Hutch News Service

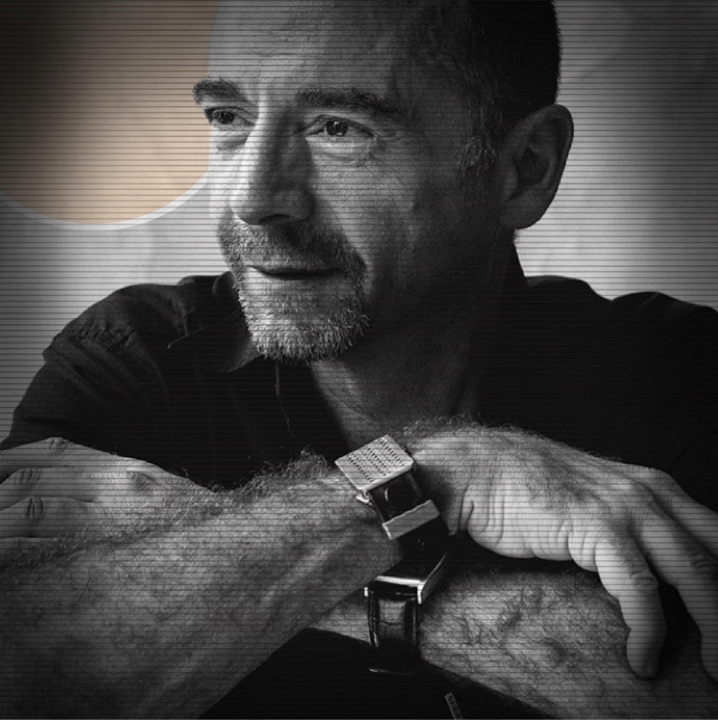

Timothy Ray Brown celebrates his 10th “birthday,” marking the anniversary of the stem cell transplant that made him the first and so far only person in the world to be cured of the virus that causes AIDS.

Robert Hood / Fred Hutch News Service

“It happened, and it was a hard survival. But I’m here.”

With these words, Timothy Ray Brown blew out 10 candles on a chocolate birthday cake as a room full of researchers, activists and people living with HIV cheered.

A decade has passed since the first of two stem cell transplants cured Brown of both leukemia and HIV, making him the first and so far only person to be cured of the virus that causes AIDS. Sunday’s “birthday” celebration, a tradition among transplant cancer survivors, capped a day-long workshop on HIV cure research on the eve of a major HIV scientific meeting, the annual Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, or CROI, being held in Seattle.

The Seattle-born Brown flew in for the workshop and celebration from Palm Springs, California, where he now lives. Later this week, he’ll mark his original birthday, albeit a little early, with his mother. He turns 51 in March.

Dr. Gero Hütter, the German doctor who cured Brown, could not attend Sunday’s party in Seattle but sent a videotaped greeting. At the time of Brown’s transplant, scientists had considered a cure for HIV so unlikely that it took Hütter a year after first reporting the case to get a paper published in a medical journal.

“I think that you all agree with me that Timothy’s case, as a proof of principle, has changed a lot of the field of HIV research,” Hütter said in the video. “Timothy is the motivation for hundreds of researchers, fundraisers and activists to go forward to the big target that HIV/AIDS can be cured.”

But if Brown’s cure inspired the field of HIV cure research, he is also a reminder of the challenges that remain.

‘The Berlin patient’

Brown was diagnosed with HIV in 1995 in Germany, where he was then living. A year later, he went on antiretroviral therapy, a medical breakthrough that transformed HIV from a death sentence to a manageable disease for those who have access to the drugs. It was not until he developed life-threatening leukemia, and chemotherapy failed, that he needed the stem cell transplant in 2007. That’s when Hütter had the idea of trying to cure both diseases at once by finding a donor with a rare gene mutation that blocks HIV’s entry.

In 2008, the cancer returned and Brown required a second transplant. But he has not taken antiretroviral medicine since the first, and today he still shows no signs of either leukemia or HIV. Identified only as “the Berlin patient” in that first paper and in subsequent media reports, Brown went public in 2010, around the time he returned from Berlin to live in the United States, as a way to call attention to the need for cure research.

No one considers a high-risk, high-cost transplant appropriate for the vast majority of people with HIV who don’t also face a deadly blood cancer. Brown’s experience shows why. The second transplant was especially hard on him and required a brain biopsy that left him with some neurological problems. Years of physical and other therapy have helped resolve that, but his eyesight is poor and the harsh chemotherapy that he underwent as part of his “conditioning” for the transplant has left him with nerve damage and balance problems. His disabilities leave him unable to work.

“Mainly, I just want my life to be normal again,” he said Sunday.

Several attempts to replicate Brown’s cure, with and without an HIV-resistant donor, have failed to show the same results. In many cases, patients died from the transplant or of their cancer before it could be determined whether their HIV was cured. In two patients in Boston who received transplants from donors without the protective mutation, HIV rebounded after several months of remission.

At Sunday’s workshop, Fred Hutch’s Dr. Hans-Peter Kiem described how he and other researchers are using Brown’s case as a starting point to find a less harsh and more broadly applicable cure. He and Dr. Keith Jerome co-direct defeatHIV, a Hutch-based HIV cure research group that focuses on cell and gene therapy. Their goal is to genetically engineer resistance in an HIV-infected person’s own blood stem cells rather than, as in Brown’s case, using immune cells from a matched donor with the rare HIV-resistant mutation. The group also is working on using the immune system to eradicate or at least control HIV, just as immunotherapies are beginning to revolutionize cancer treatment.

DefeatHIV is one of six public-private research groups nationwide funded by the National Institutes of Health to research potential HIV cures.

“I really want to thank Timothy,” Kiem said Sunday. “He really inspired and launched cure research.”

‘You give me hope’

When antiretroviral therapy was first introduced in 1996, hopes were high that, taken long enough, the drugs would not just suppress but cure HIV. These hopes were dashed when researchers found that the virus integrates itself into some of the longest-lived cells in the body, forming reservoirs of latent infection that roar back if medication is stopped.

But according to studies presented Sunday by Dr. Merlin Robb of the U.S. Military HIV Research Program, early treatment with combination antiretroviral therapy is at least a step toward curing HIV. Starting treatment very early after infection can reduce the size of the reservoir in the first place and prevent further damage to the immune system, making any cure developed down the road more likely to be effective, Robb said.

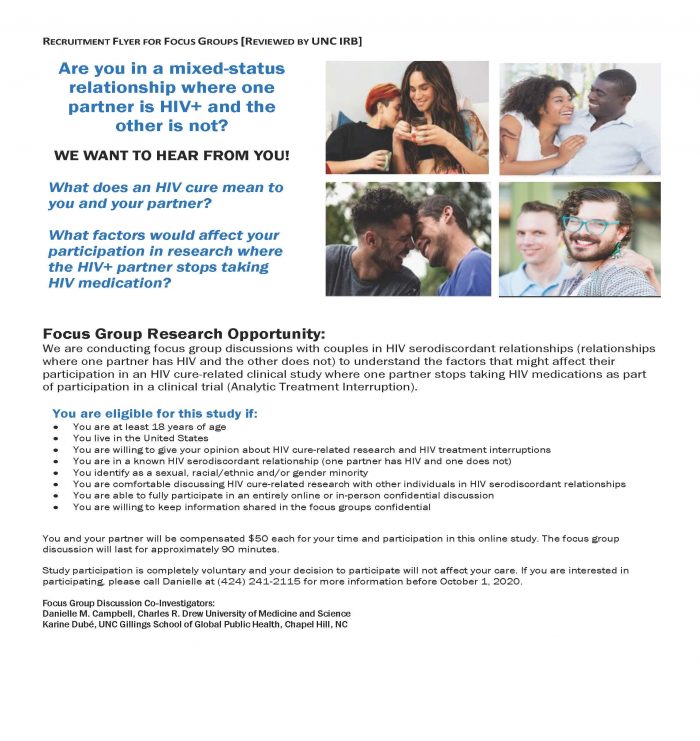

Other topics of discussion at the workshop included how and whether antiretroviral treatment can be safely halted under carefully monitored conditions to test if a cure approach is working (do not try this at home) and whether enough females, from mice to humans, are being enrolled in clinical trials to understand how cure approaches may work differently in different genders (no).

The workshop also focused on the how as well as the what and why of cure research. Laurie Sylla, a member of the defeatHIV community advisory board, which co-sponsored Sunday’s workshop, talked about how trust and transparency are key to HIV cure or any clinical trials.

Trial participants “want to know what are the risks we know about, and what are the risks we may not know?” she said. “And they want to there’s a safety plan. What’s going to happen to me if I participate in this? How quickly are we going to be able to identify that I’m having a bad reaction? And how quickly are you going to do something for me if that happens?”

Pat Migliore, another defeatHIV community advisory board member who has been living with HIV since 1984, recounted a list of fears involved in HIV cure: that long-time survivors like her will be left behind. That postmenopausal women will be left behind. That people of color will be left behind.

“Until there’s a cure for everybody in this world, there’s a cure for nobody,” she said.

As to whether there will be a cure in her lifetime, Migliore, 60, confessed to skepticism.

But, she added, “What gives me hope is seeing all of you. And Timothy, you give me hope.”

A role model, again

For all of the setbacks he has suffered and the disabilities he continues to confront, Brown, an early gay activist who once modeled himself after Boy George, retains his dry sense of humor and wicked sense of fun. He finds purpose in his role as the only member of a singular club and cheerfully embraces his role as symbol of hope.

And on Sunday, he stepped forward to be a role model once again. The only person in the world who has been cured of HIV revealed for the first time publicly that, several years ago, he started taking PrEP — for “pre-exposure prophylaxis — a daily pill that lowers the risk of acquiring HIV. Although Brown’s immune system is now HIV-resistant, he could become reinfected should he be exposed to a less-prevalent strain of HIV that uses a different kind of receptor to enter cells.

Brown recognizes how devastating it would be to people who take hope in his cure for him to have HIV again. And if the most famous HIV-free person in the world can be an example to others at risk of contracting HIV to use PrEP, then Brown is up for the task.

As Moses Nsubuga, an HIV activist and musician from Uganda in town for the workshop and CROI, sang a Ugandan birthday song and everyone else gamely joined the chorus, Brown basked in the appreciation and declared he could handle blowing out the 10 candles.

“It’s OK,” he said, before taking a big breath. “It has worked out.”

Join the conversation about an HIV cure on our Facebook page. Learn more about HIV/AIDS research at Fred Hutch.

Mary Engel is a staff writer at Fred Hutch. Previously, she covered medicine and health policy for newspapers including the Los Angeles Times, where she contributed to a series that won a Public Service Pulitzer for health care reporting. She also was a fellow at the year-long MIT Knight Science Journalism program. Reach her at mengel@fredhutch.org or follow her on Twitter, @Engel140.

Are you interested in reprinting this story? Be our guests! We want to help connect people with the information they need. We just ask that you link back to the original article, preserve the author’s byline and refrain from making edits that alter the original context.